High expectations and a palpable sense of self-seriousness drag GDT’s long-awaited opus down.

Guillermo del Toro‘s Frankenstein has been a long time coming. The Mexican filmmaker, arguably our premiere screen fantasist right now, has long made his admiration for the novel, the 1931 James Whale film, and pretty much every iteration since, quite plain. Speaking to Den Of Geek in 2016, he called Frankenstein “the pinnacle of everything” but noted his reservations at trying to mount his version.

“I dream I can make the greatest Frankenstein ever, but then if you make it, you’ve made it. Whether it’s great or not, it’s done. You cannot dream about it anymore. That’s the tragedy of a filmmaker.”

Well, it’s here now, or will be soon for the general public, and it turns out del Toro’s misgiving were well-founded. His Frankenstein, starring Oscar Isaac as the titular brilliant medical student driven to dabble in the unknown and Jacob Elordi as his monstrous, Miltonian creation, is a mess.

It’s a well-intentioned mess, mind you, and it’s a very GDT mess, crammed full of the images, themes, and general aesthetic he’s known for. Crammed to bursting, in fact. It’s a self-indulgent film, but also an uncomfortably constrained one. You can feel del Toro’s self-doubt, and it’s warring with his drive to imbue this Frankenstein with everything he’s ever thought or felt about the horror icon. But in trying to do so, he’s left no clear thematic thread for us to follow. While the events of the story play out in more or less the manner to which we’re accustomed, we’re given little reason to care.

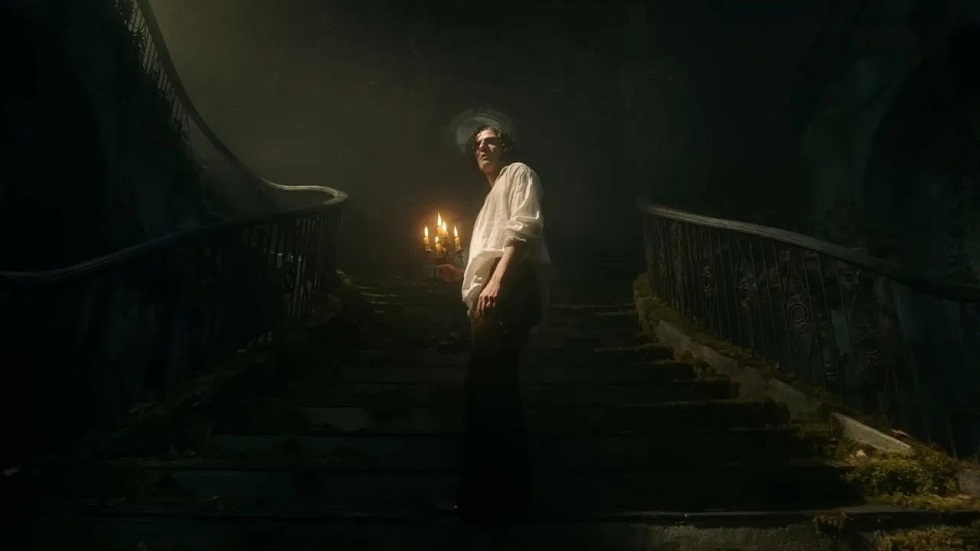

It looks fantastic, though, from the early Arctic scenes where an exhausted and wounded Frankenstein narrates his tale of woe to Lars Mikkelsen’s ice-bound explorer, to the gloomy gothic tower where Victor conducts his experiments, to the design of Elordi’s gaunt and hulking creature (the debt owed to Bernie Wrightson’s illustrations is huge). The production design is as intricate and sumptuous as you could hope for. There are moments of gore and horror that are incredibly striking. And the whole thing is as dull as ditchwater.

The film, quite simply, is a slog – a turgid, unengaging, self-serious palimpsest of what has gone before that does little to justify its whopping 150 minute running time. There’s no sense of rising action or stakes; we never feel as though this thing is going anywhere or building to something; it just goes on and on until it suddenly doesn’t, wrapping with a pat moral lesson about the dangers of obsession that, while certainly a theme present in the source material, is not the dominant motif in what has gone before.

No, up until that point del Toro’s Frankenstein has been a fairly Oedipal affair, with Isaac’s Victor certainly wanting to murder his cruel disciplinarian father (Charles Dance) and bone his constantly scarlet-clad mother (Lauren Collins) but is robbed of both opportunities when they die on him. She dies giving birth to Victor’s younger brother, William (Felix Kammerer), giving the elder Frankenstein motive to resent his sibling.

That might also partly motivate his choice to horn in on William’s fiancée, Elizabeth (Mia Goth) when she hoves into view, but never fear, she’s another in del Toro’s long line of self-possessed monster fuckers (see: Selma Blair in Hellboy and Sally Hawkins in The Shape Of Water) and is far more drawn to Elordi’s Creature. Being the first woman he’s ever clapped eyes on, she’s a mother figure, too, and so the Oedipal cycle reiterates, with Victor as the Bad Dad.

Elizabeth and the Creature are both slaves in their own way, of course. When she meets him he’s chained up in Victor’s basement, cringing like a beaten dog (Victor’s sudden switch from driven scientist to tormentor does not convince). Elizabeth, although engaged to William, is all but dangled in front of Victor by his financier, Henrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz), used as a bargaining chip to encourage Victor’s experiments in raising the dead. It’s later revealed that Harlander’s interest in defeating death is, in its own way, sexual – he’s dying of syphilis.

Which all sounds interesting! And certainly allays one main worry leading up to release – that del Toro would be too beholden to the source material to much with it. As it turns out, he’s not afraid to make plenty of changes, large and small – Herr Harlander is a new addition entirely – but the reasons for those changes remain murky. For one, I cannot figure out why the timeline was moved to the 1850s, well after the 1818 novel was published.

The cast are engaging, though, and none so much as Elordi as the Creature, although he does have to endure an awkwardly funny introduction, his initially hairless and pallid form drawing unintended laughter from the preview audience. Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 effort, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, had a similar sequence of unintended comedy where the director, also playing Victor, wrestled with Robert De Niro’s recently animated monster, but what they really have in common is that both could have been cut with nothing of value lost.

And that’s the real issue with del Toro’s Frankenstein: his adaptational choices make no sense. Adaptation is a tricky thing. It’s a process of reduction and concentration, but also selection; you need to decide what themes and events to highlight and what to discard. Del Toro’s weirdly grab-bag approach, presumably made in attempt to encompass everything that Frankenstein means to him, results in a sluggish and overstuffed film, a patchwork effort that never fully comes to life. You can’t fault the ambition, but this is a failed experiment.

Frankenstein is in cinemas from October 23, and on Netflix from November 7.