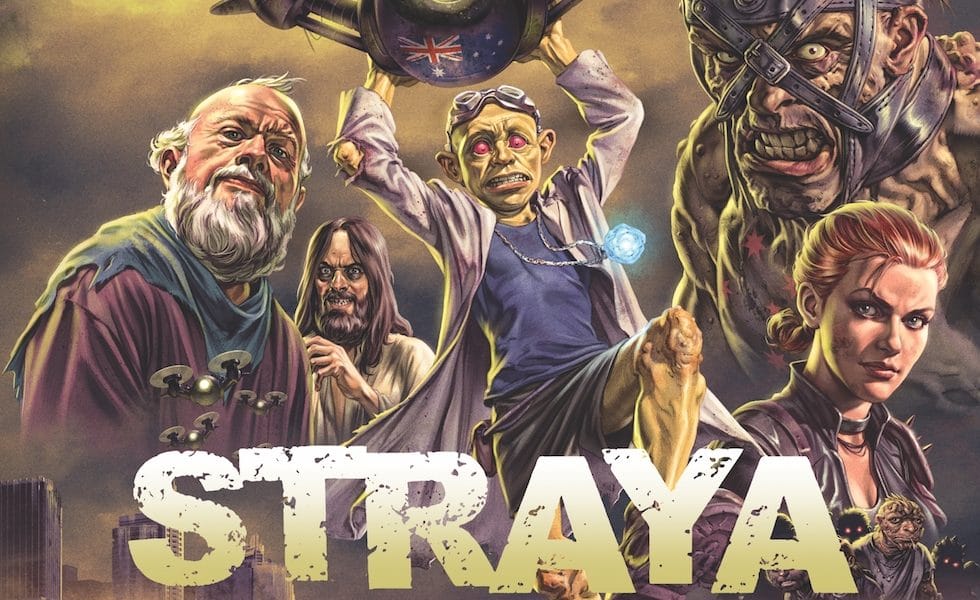

Strap in for a rip-roaring ride through post-apocalyptic New Sydney as Travis Johnson chats with critic-turned-author Anthony O’Connor about his debut novel.

Young Franga has problems.

He’s poor, he’s put-upon, he has a massive and unrequited crush on a kind-hearted sex worker, and he’s a bald, yellow-skinned, crimson-eyed mutant outcast living in the dystopian hellhole that is the Inasiddy of New Sydney, circa… well, no one really knows, but a while after everything went to hell.

It’s a tough life, but things start looking up when Franga finds a weird technological artifact in the ruins of the city that might spell a new lease on life for its beleaguered citizens – or possibly the end of all things. It’s a toss-up.

Featuring a full ensemble of mutants, monsters, chancers, rebels, religious nutters, cannibals, and more, Straya comes to us from the fevered mind of screenwriter and film critic Anthony O’Connor (Angst, Redd Inc). Written in an Aussie patois in much the same way Trainspotting was written in Scottish, it’s a madcap rampage through the blasted ruins of Australian culture. Violent, profane, and laugh out loud funny, it’s quite simply the most Australian sci-fi novel since…well, ever.

Where did the idea for Straya come from?

Straya has been with me for decades. I first had the idea when I was a wee lad – I’m thinking twelve or thirteen? Something like that? Anyway, the concept was broadly speaking the same. Ruined city, personality-absorbing monster, shenanigans ensue. It was called Body Chute back then, and what it was missing was a point of view character.

Originally the premise was, a cop from the Big End of Town and a cop from the Inasiddy would team up to try and take the monster down. I was pretty obsessed with 2000 AD comics, Judge Dredd in particular, and Blade Runner, so I suspect I was doing my best to ape those influences. The problem was, I didn’t know (or much care) about cops and I certainly didn’t have any insights to offer about them, so the story never went any further.

I’d dig it out every now and then, remind myself why I liked the world so much, and then just get on with something else. So, years later, around 2017, I start having these ideas about a troupe of teenage mutants who put on plays to amuse people in the ruins of a city. And then, emerging like a beast from the Downlow, I remembered good old Body Chute and thought, “Hey, let’s smush those two together and see what happens!”

Was it always your plan to write in a fractured version of the Australian dialect?

I’ve always been obsessed with Australian slang, and the sheer diversity of Aussie accents and colloquialisms, so it was definitely something I wanted to explore. I’m not sure if I consciously wanted to do it in Straya at first, but as soon as I worked out who Franga was, I knew he had to talk a certain way. The balancing act was finding a way to make it engaging, but still comprehensible. I used books like A Clockwork Orange and Trainspotting as guides, because they pretty much set the benchmark for made up languages and phonetic Scottish respectively.

Was it hard to write a whole book in Strayan?

I mean, it’s hard to write a whole book full stop. It takes ages, you spend most of the time in a dank sub-basement and by the end of it you resemble a clammy-skinned mole person, fearful of sunlight and human contact. I’m not sure it’s any harder doing it in Strayan. Once I’d worked out the terms I wanted to use, and the way everyone spoke, it was book writing business as usual.

Where does Franga come from? Or to put it another way, are you Franga?

So, look, there’s this thing writers do sometimes, where they talk about how a character came to life and somehow wrote their own story, against the author’s will. And I always think, “You affected wanker, shut your lying noise hole.” But I swear a version of that happened to me writing Straya.

Franga was originally intended to be much more of a glib smart arse, aloof and cynical, and yet as I was writing he just kept being kind. I fought it for a while, but he consistently resisted the temptation to be a prick. Eventually, I just leaned into it, and embraced the fact his kindness was his strength. So, yeah, Franga is lovely and wonderful and I am definitely not him.

How did you go transforming contemporary Sydney into the setting of the book?

Lots of walking around Sydney, imagining how things could be used by a kind of makeshift, devolved society and taking notes. It’s been a bit of a lifelong obsession, really, imagining a post-apocalyptic society. I was a nipper during the 1980s, so I caught the full brunt of that Reagan-era nuclear war terror and never quite shook it. The specifics of the apocalypse in Straya are deliberately vague, but the notion of it defo comes from that decade when we all cowered in the shadow of the mushroom cloud that thankfully never arrived.

You’re a screenwriter and a film critic – what led you to working in prose?

Well, I’m a voracious reader and I’ve always wanted to write books. So that’s reason one. But there was an element of necessity too, because the Aussie film industry, as it currently stands, doesn’t seem to want to tell the Mad Max-style genre stories it used to in the ’70s and ’80s, or even the weirdo indie yarns from the ’90s. And that’s fine, times change and all that, but I wanted to tell an odd, ambitious, apocalyptic story that resists easy categorisation, and a book seemed the ideal medium. That said, I’d be more than happy to knock out the screenplay as well. Someone get George Miller on the phone!

Is this a one-and-done, or is there more Franga and Straya to come?

I wanted Straya to feel like a finished product, a complete story, that was first and foremost. But I would absolutely love to tell more stories in this world, with Franga and New Sydney and the parts of Straya that we haven’t visited yet. So, yes, I have a whole bunch of yarns ready for the telling, if there’s a demand for it.

There’s a lot here about the value of the ‘Yarts’, particularly for the disenfranchised. Is that something you’re passionate about?

Oh, absolutely. Look, the arts (‘Yarts’) should be for everyone. This notion they’re a preoccupation of the idle rich is maddening and relatively new, historically speaking. I don’t know how you’d make them accessible across the board, but I do know that as long as you have to hock a kidney to be able to afford a trip to the Opera House, they never will be. The arts enrich us, and I reckon everyone deserves to be enriched.

Except people who use their phones during plays. They can get stuffed.

Apart from Franga, what character resonated the most with you?

Oh, it’s 100% the monster, hey. One. Hundred. Percent. I’ve always empathised with the monster in this kind of gear. I remember when I was kid, I saw Clash of the Titans (1981) and I was absolutely inconsolable when the Kraken died, because to my young mind it wasn’t evil, just misused by one dickhead God or another. All monsters are tragic in a way, Straya’s monster certainly is. They’re usually victims of circumstance, or humanity’s hubris. It’s what makes them so interesting.

The above-mentioned aside, what other books, movies, etcetera influenced you?

I reckon John Carpenter is probably my biggest cinematic influence. I mean, The Thing, Escape from New York and They Live alone are superb and iconic. I always loved the slightly demented works of Frank Henenlotter, especially Brain Damage and Basket Case. God, David Cronenberg, Dario Argento, George Romero, Tom Savini. I could bang on about it all day. For books? Gotta be Stephen King, Joe R. Lansdale, Jack Ketchum and Guy N. Smith.

Why does Guy N. Smith loom so large in the mythology of Straya?

I mean, the guy wrote ten books and one short story collection about killer crabs, he’s basically pulp fiction royalty. But he was one of the first horror authors I ever read, and I adored the sheer unpretentious glee with which he spun a yarn. He wrote books that impressionable teens could get utterly lost in and I never forgot that feeling, a feeling I eventually gave to Franga.

I was actually going to send a copy of Straya to Guy N. Smith but he passed on before it was ready. It’s one of my biggest regrets that I didn’t reach out earlier and thank him for his fine works. As Franga would say, he’s truly one of the grousest murder-poets.