One thing we don’t talk about much, or maybe just not often enough, is how movies are really time machines.

I don’t mean in the way that they can be set in far-flung times and places, putting the viewer into medieval Europe or ancient Rome or colonial New South Wales or what have you – that’s pretty obvious, and subject to the inevitable push-pull between historical accuracy and narrative necessity (Braveheart, for example, is a hell of a film but a terrible historical primer). I mean in the way that when someone appears in a movie, especially a successful one, they’re immortalised in a small but significant way. They’re locked at that time of their life, frozen but moving. The real “them” gets older, probably does other movies, lives a life, maybe (well, certainly at some point) dies. But that “them” on the screen? Immortal. Humphrey Bogart will always be saying goodbye to Ingrid Bergman on the Casablanca airfield. Robert De Niro will always be asking the mirror if its talking to him. James Dean’s parents will always be tearing him apart.

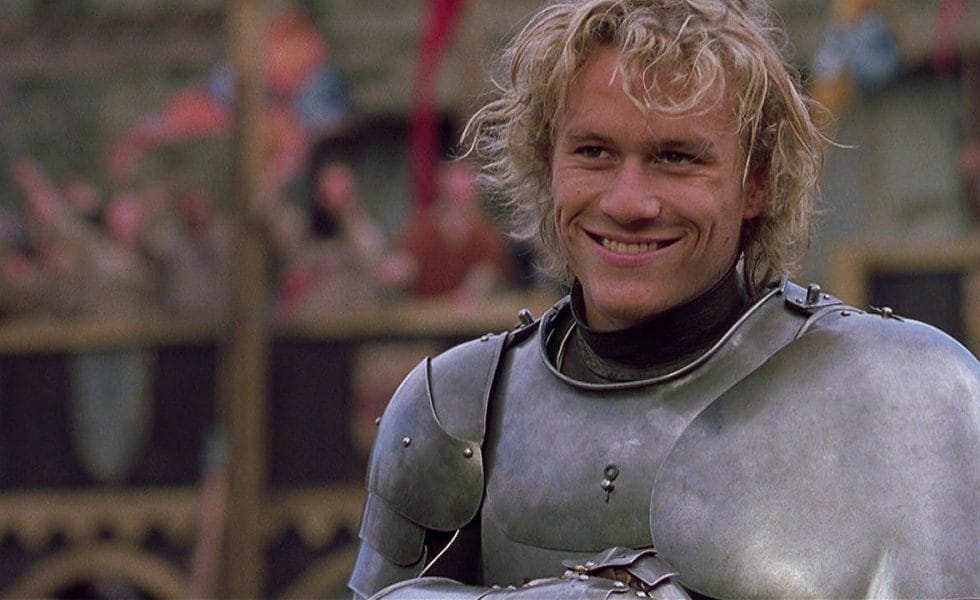

And Heath Ledger will always be jousting in the lists.

Released back in 2001, the gleefully anachronistic, utterly stirring medieval adventure, A Knight’s Tale, was an absolute crowd pleaser. Critical response might have been mixed but global audiences threw US$117.5 million at it, almost doubling its US$65 million budget. Watched today (it’s right there on Netflix) it’s still a barnstorming good time, but that enjoyment is tinged with melancholy because, as we all know, Ledger, then on the very brink of stardom, would be dead of an accidental overdose less than seven years later.

So yeah, it’s a little eerie revisiting the film knowing that Ledger is now in his grave at Perth’s Karakatta Cemetery, only 28 years old when he passed. But the immortal young Ledger we see on the screen? My god, what an absolutely star-making turn. This wasn’t his first at-bat; he’d done TV and Australian film, got good notices for his leading role in 1999’s Aussie crime drama Two Hands and had played opposite Mel Gibson in the 2000 historical drama, The Patriot. Shakespearean rom com 10 Things I Hate About You had cemented his teen heartthrob status, but it was in A Knight’s Tale where it all came together.

The plot is a simple enough underdog rags-to-riches affair, made exotic by being set on the jousting tournament circuit of the 1370s. When his noble master keels over dead prior to an important match, peasant squire William Thatcher (our boy Heath) straps on his armour and steps into the stirrups. Initially it’s an act of desperation; the prize money means food in the bellies of Will and his fellow serfs, pragmatic Roland (Mark Addy) and angry AF Wat (Alan Tudyk, amazing). But Will has a taste for glory and soon impersonating a knight is a full time gig, thanks to forged papers from itinerant writer Geoffrey Chaucer (Paul Bettany) and fresh plate from armourer Kate (Laura Fraser). He even romances the noblewoman Jocelyn (Shannyn Sossamon) but finds high-handed jousting champion Count Adhemar (Rufus Sewell) blocking both his romantic and sporting aspirations.

Which is all fairly generic – the “slobs vs snobs” narrative model transposed to a medieval setting. But right out of the gate writer and director Brian Helgeland (L.A. Confidential) lets us know that we’re not in for the usual mud ‘n’ blood Middle Ages posturing: the thronging crowd at our first tournament are chanting along to Queen’s “’We Will Rock You’, and it goes off like a frog in a sock.

Anachronism is nothing new to the historical subgenre and is usually invisible to anyone without a strong interest in history (I have historian and archaeologist mates who will tear any given Hollywood historical a new one at the slightest provocation). Helgeland doesn’t hide his anachronisms; he puts them right up front and demands that we grapple with them. They’re not mistakes or the result of sloppy research; they’re deliberate and they have a point.

That point is largely tonal. If you want to get the crowd revved up you could do a lot worse than ‘We Will Rock You’, Thin Lizzy’s ‘The Boys Are Back in Town’ or AC/DC’s ‘You Shook Me All Night Long’, which additionally feature on the soundtrack. But it’s also about genre identification. This isn’t a tale of bloody battles and brutal misery; A Knight’s Tale is a sports movie, and the soundtrack cues help us plug into the narrative rhythms thereof, moreover priming us to be receptive for the film’s progressive (for the time) attitudes to gender and class. Plus, seeing those armoured knights get knocked off their horses in glorious slow motion to the strains of classic rock is never not a fun time.

But it’s also just showing off, which I appreciate. A Knight’s Tale isn’t anachronistic because it’s dumb, it’s anachronistic because it’s smart, and while some might harrumph at a period piece set to ‘70s rock bangers, that’s missing the point. This is a film smart enough to have Chaucer as a major character, and Edward the Black Prince (James Purefoy) in support. Tudyk’s near-rabid Wat is almost certainly named for peasant revolutionary Wat Tyler, which may be the deepest historical cut in the movie. The balance between historical trivia and big, broad populism is perfect.

Still, the film’s big strength is its cast, and it’s fascinating to look at the ensemble in light of where they were at the time and where they were going. Genre TV mainstay Tudyk is simply wonderful as the incredibly angry Wat, while Mark Addy, a few years out from sudden international prominence off the back of 1997’s The Full Monty and yet to rule the Seven Kingdoms in Game of Thrones, has that common-sense deadpan delivery cold. Shannyn Sossamon is simply luminous as the love interest, even if she’s given little else to do apart from looking luminous, and Rufus Sewell, who just has one of those villainous-looking faces, all but twirls a moustache as the villain, completely understanding his function here and embracing it with gusto. And then there’s Paul Bettany, gleefully chewing the scenery as William’s herald and hype man, clearly relishing getting his tongue around the best dialogue in the film as he pumps up the crowd with his master’s mostly fictional accomplishments.

And needless to say, there’s Ledger.

Tall poppy syndrome being what it is, it’s simply not the done thing in Australia to acknowledge that any public figure might actually be good at their job, but to hell with that. Ledger was a captivating screen presence, and while as his career progressed he leaned more towards idiosyncratic character roles (what else is the Joker if not idiosyncratic?), here his powers as an old-fashioned marquee star are on full display. He looks the business with his tousled hair and square jaw, and he wears that armour like he was born to. Most importantly, he sells William’s drive to raise himself up higher than his birth destiny, to not be constrained by circumstances or society. For all his movie star good looks, the character is identifiable and relatable – the performance makes us believe that this idol is an everyday guy in the universe of the film, if only for the running time.

He’s gone now, of course. And he’ll be with us forever. It’s the weird paradox of movie immortality. Ledger made better films and turned in better performances over the course of his short career, but A Knight’s Tale stands as the perfect encapsulation of his appeal, his talent, and his craft.