In 2014, when Richard Dorrough walked into a gun range and shot himself, he wanted to be noticed. When he left a note in his belongings admitting that he’d killed three people, he wanted his story to be told. With the Audible original Bloodguilt: The Many Deaths of Richard Dorrough, his story is now being told, though not as he intended.

Please note: The following article and podcast series discussed include the names, images and stories of First Nations people who have died.

Hosted by Walkley award-winning journalist Kate Wild and Dan Box, working alongside audio producer Selena Shannon and producer Ivan O’Mahoney, Bloodguilt takes a sharp turn off the well-worn true crime path, veering into new territory both creatively and morally. The resulting story is one far more concerned with the victims, their families, and the potential impacts of reliving the details of their loved ones’ murders than with the man who murdered them. The result is a true crime story uniquely powered by empathy and respect rather than shock and horror.

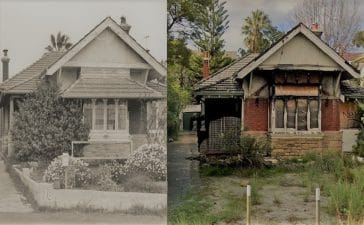

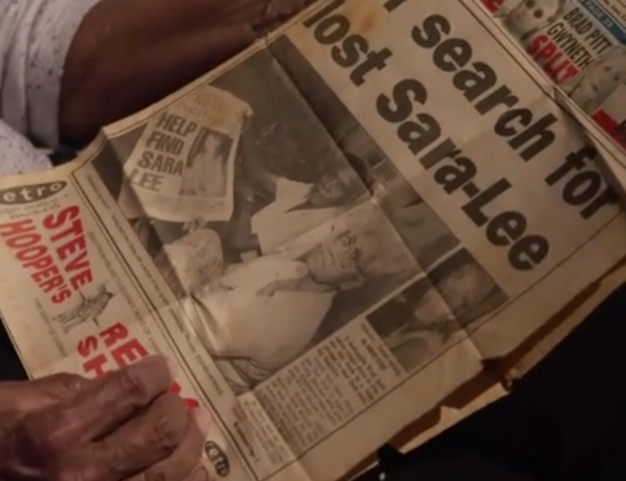

Applying a different lens through which to view the objectively shocking and horrific details of the murders of Rachael Campbell, a Māori woman who migrated to Sydney from New Zealand and Sara-Lee Davey, an Indigenous woman from Western Australia, came from a need to avoid what Wild describes as “the true crime cookie-cutter template”.

“You have the true crime template,” She expands. “The terrible murder, invariably, of a young woman. The serial killer. The detective – or cop of some description who either might be the hero or is the person who stuffed everything up. The heartbroken family members. The questioning neighbour. You’ve got these set characters that exist in the story. You find them, you slot them into their places, and away you go. You don’t look off the road at all.”

Bloodguilt speaks to the fact that these aren’t just plot points or subjects, these are “people who’ve already been traumatised on so many levels.”

“The way we report true crime is often quite schlocky; we do it as entertainment,” Box adds. “You have to have a reason to essentially rake over the tragedy of someone else’s life. We went into two families, well, three, in a way. And basically said, ‘Look, we’d like to talk to you about the worst thing that’s ever happened to you.'”

“We’re constantly saying to ourselves, ‘Is this right?'”

It’s that healthy scepticism of their work that makes Bloodguilt more compelling. Whereas most true crime fare simply ask, “who done it?” Bloodguilt goes further, seeing Box and Wild question their own motives, the risk of adverse impacts and their right to be bothering anyone, at all.

“I can say 100% my biggest pet hate with journalism, whether it’s podcasts or anything else, is this voice-of-God journalism.” Wild explains. “Sure, you can check your facts, you can get the story from lots of different people. [But] no one is the great authority on anything, even the person it happened to.”

Ultimately the most important question Bloodguilt asks is: “Why does this keep happening?”

Bloodguilt is a story without a tidy ending, most notably because of the absence of a clear third victim. “This is not a story that can end”, Wild says, “because violence against women is endemic.”

That’s not to say it doesn’t have a conclusion – because it does, a call to arms. “I still haven’t given up on that hope,” Box admits.

“In the process of reporting on these cases that are linked to Richard Dorrough, we stumbled over so many other cases that were kind of tangentially related…A woman who was murdered in Sydney the same weekend as Rachael Campbell. The cousin of Sarah-Lee Davey also disappears, was never found…Violence committed on the edges of these stories, always against women and often unresolved by the police or the prosecuting authorities.”

“I think it’s amazing that we ever solve a crime.” Wild offers. “No one gets enough time or enough space to do all the work that is possible on a case. When you build those up, when you build into that lack of time and lack of space, the unconscious biases that we also bring to the work that we are doing, you start to see the layers of challenge and the layers of hurdles.”

Bloodguilt puts forward another hard truth – that while the media certainly aren’t guilty of the crimes they report, they certainly aren’t blameless. “I didn’t have any plan to start talking about the media, or about social perception of these women or about the perception within the police of these women. But once we started doing it, it became obvious. You couldn’t tell the story without talking about those things.”

“When you sit down with sister of a woman who’s been murdered and seen her sister described as a Sydney prostitute [in headlines], that’s when you realise the harm you do through these little choices as a journalist and just the language you use,” Box says.

Wild also sees an opportunity for journalists to “tell our stories better,” and points to another conclusion arc for Bloodguilt – the upcoming Senate inquiry into the missing and murdered women and children of First Nations in Australia.

“Pretending that we neatly racked this story up would just be false.” She adds: “The fact that other people are taking this seriously and want to know more about it, that there’s a Senate inquiry into it, I think that’s the closest thing to a note of hope that you could find in what’s a pretty dark story.”

Bloodguilt: The Many Deaths of Richard Dorrough is streaming now on Audible.