It was 1993, and according to Juice founder Toby Creswell, “if music didn’t have a guitar and a drum, people weren’t interested.”

Magazines were, at the time, a driving force behind the culture and music scenes–where people now turn largely to the internet for inspiration, magazines would serve as the overarching experts of what is both cool and up and coming.

In the early 90’s, the popular music scene was dominated by a new genre emerging from Seattle, dubbed Grunge. This eventually swung English, with the inception of both Blur and Oasis, and additionally saw the emerging popularity of indie films, hip hop, dance music and rave culture follow.

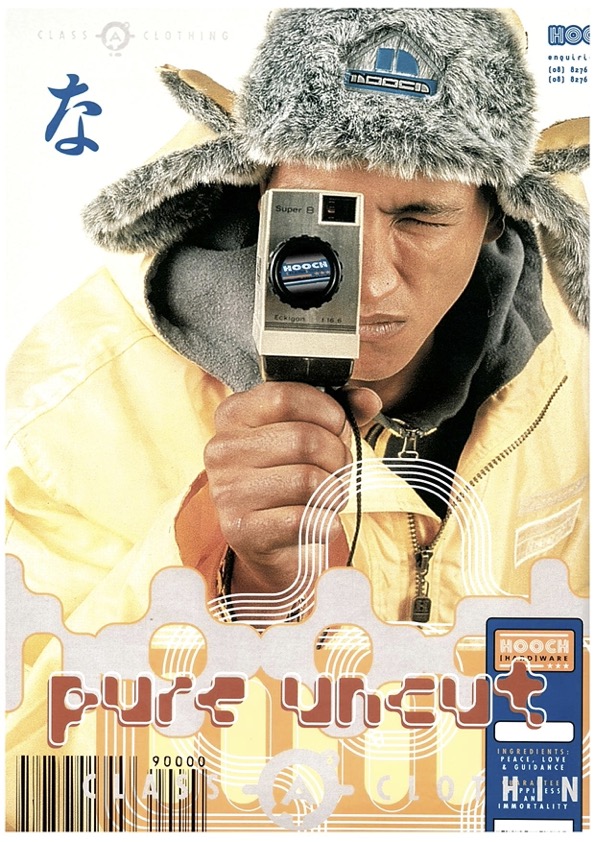

Overall, the cultural shift was leaning alternative, bringing along with it a generational shift in attitudes. The media, more than ever, was focusing their attention towards young people. There were now two music categories to consider-mainstream and alternative -and the assumption was that if you were under 25 and cool, you would be listening to alternative music.

Industries began devoting their energy to entertaining young audiences, which brought along with it legendary Australian institutions such as the Big Day Out festival, and the publication Juice. I spoke to Creswell about how it seemed that history was changing, and why he wanted to be on what he considered “the right side of history.”

“There was a world before Nirvana put out Nevermind and there was a clear world after that,” Cresswell says.“You either had to drink the Kool-Aid or not. I guess that was the context in which we were trying to do Juice.”

The Beginnings of Juice

Toby Creswell, alongside Lesa-Belle Furhagen and John O’Donnell were the founding forces behind cultural zeitgeist, Juice. Beginning his tenure with Rolling Stone during his university days, Creswell wrote for the publication for a number of years before becoming Music Editor.

From their beginnings at the title, Creswell, Furhagen and Philip Kier co-drafted a proposal to Rolling Stone America to take over the Australian franchise. Eventually, creative and personal differences led to the deterioration of their partnership, and to Creswell and Furhagen simultaneously leaving the publication in 1992 to found Terraplane Press. This consequently prompted the creation of Juice in 1993, going on to serve as a direct competitor to Rolling Stone.

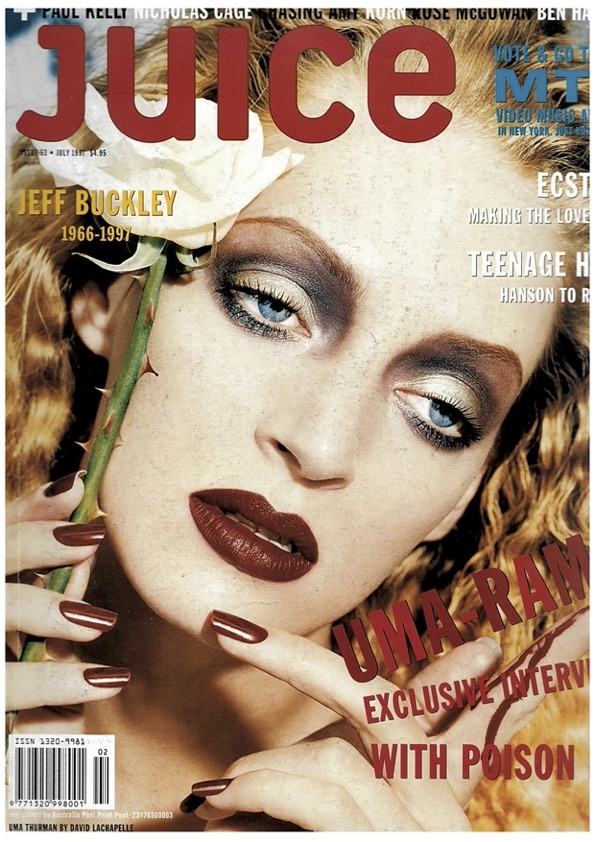

Juice was almost an immediate success following its first edition published in March 1993. It filled the said emerging space in youth media with its conversational and raw tone of voice, which looked to meet the readers where they were, with the language they had, rather than with an authoritative, industry voice.

From here, the publication continued to churn out thirteen issues each year, including their annual yearbook edition. Alongside pieces from their in-house and freelance writers, the publication paired up with another competitor of Rolling Stone, American magazine Spin, to license a select number of pieces to feature in each edition. This was only made possible in the absence of the internet, as Juice’s Australian readership wouldn’t otherwise have access to these pieces.

The Beating, Cultural Heart

Juice’s staff were the driving force of their cultural stance, as they were all very much part of the local cultural scene. Founding editor, John O’Donnell, was a staffer who was deeply embedded in the music industry. Eventually O’Donnell left Juice in 1994 for Sony Music Australia’s alternative record label Murmur, at which his first signing was the band Silverchair.

Following John’s departure, the editor role was taken up by Rob Johnson, who was brought into the Juice team, initially as Associate Editor, following his freelance work with Rolling Stone Australia. Johnson described both O’Donnell and Creswell as being incredibly knowledgeable about all things music, film and popular culture -they were well-connected and deeply engaged with the culture of the time -informing the magazine’s on the ground approach.

“We went out a lot, it’s definitely the way to do it. Even nowadays when things are so accessible, somebody’s gotta find someone first, and the best way to do that is to be involved with it all,” Creswell says.

O’Donnell also noted that their Oxford Street location, with institutions like Sony Records and Universal Music right around the corner, meant that there was always close access for the publication with artists and agents often calling in, sometimes unprompted like old friends, to provide insight, for interviews or just to chat.

Keeping It Local

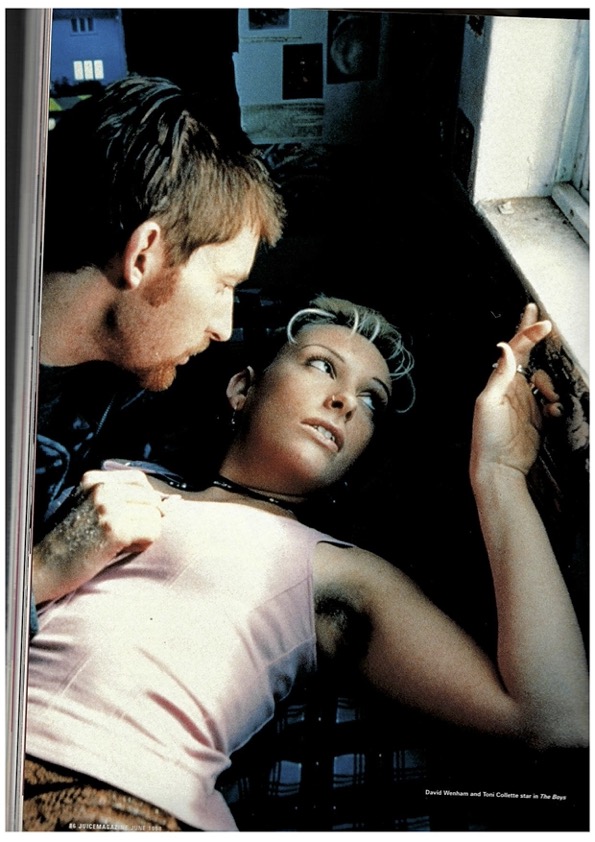

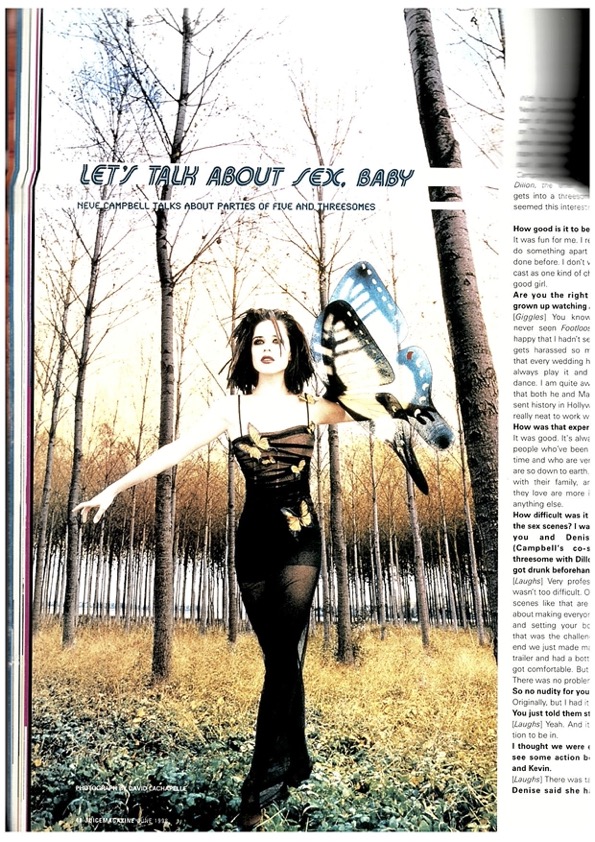

Their team was small but mighty in the beginning, all sharing a passion for fostering the magazine’s historical shift inward-championing artists of all sizes but with a large focus on Australian talent. Big artists and celebrities, such as Ice Cube, Drew Barrymore, Lauryn Hill and Oasis were often placed next to independent or up and coming domestic artists in each edition, with the goal of piercing the thinly-laid veil of stardom.

Juice’s work to champion independent Australian artists, at the time, was second to none. In a time before digital media, print was the driving force behind garnering the kind of public recognition that could single-handedly catapult a career. This has inarguably laid the foundation for modern Australian artists to be the most successful they’ve ever been.

“I remember when we took over Rolling Stone Australia and it was a big deal that Crowded House and INXS were getting reviewed, and now people like Troye Sivan and Amyl and the Sniffers are massive globally in a way that they’ve never been before,” Cresswell recalls.

A Digital Revolution

The publication’s move to digital was in 1999 and garnered an enlivened response from their readership, with over 60,000 visitors on the first day. The site, which was updated daily, offered music news, videos and reviews, as well as a free email service and message boards. Creswell cited the motivation of this shift as simply “because it was exciting.”

Cresswell remembers talking to people about the internet when it started. They would say “digital will never replace print, people will never stop buying the Sydney Morning Herald on a Saturday.”

Changing Tides

Reflecting on the publication’s closure, shortly following its sale to Seven Network’s Pacific Publications in 2003, Creswell believes that Juice was undoubtedly underutilised. He noted that the team was incredibly hardworking, and always coming up with creative, lateral solutions to remain afloat in a -put simply- brutal industry financially.

In retrospect, if Juice had its time again, Creswell hopes that the magazine would be bigger, and wilder, than before -citing missed markets such as gaming, and extreme sports -”I think we got that balance wrong,” he says.

“It’s always going to feel like there’s more that you could have done and in the direction that you could have gone. Even if [Juice] was still going today, it would be very different than it was then,” former Juice editor Rob Johnson says.

With nostalgia undoubtedly being king at the moment, this retrospective dive into a legendary Australian publication feels more necessary than ever. To speak to the figure heads of this time allows us to pull back the curtain and see what was really happening in the industry at this time, and from this, think about how we can push forward in the media industry today.

Creswell’s advice to those working in and passionate about the Australian media sphere is to be more original, more provocative, more opinionated, and more risky with your work.

Johnson believes that nostalgia will live on forever, and encourages everyone to always make the most of it.

“When I was at Juice, people were nostalgic for RAM Magazine. I think that’s a normal response to the sort of cultural milieu that surrounds music,” Johnson says.

Juice may be gone, but its fingerprints will forever remain spread across the pages of Australia’s cultural history.