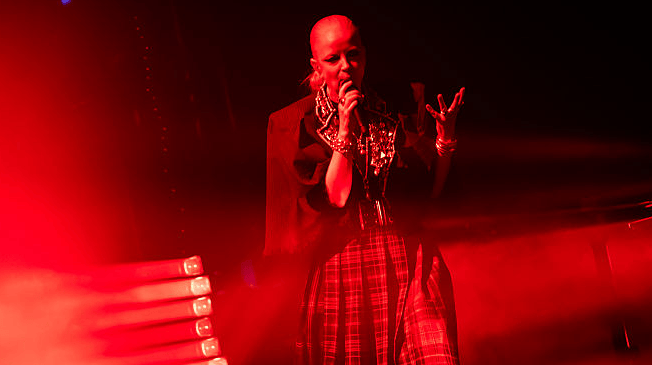

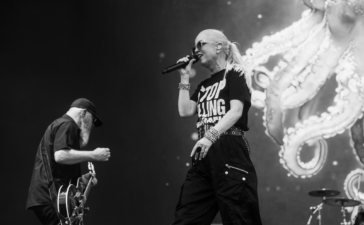

Garbage closed out their Australian and New Zealand tour at the Sydney Opera House on Sunday night, performing just hours after a mass shooting in Bondi left Sydney in shock.

During the show, frontwoman Shirley Manson paused to address the audience about violence and intolerance, urging unity in what she described as an increasingly frightening and hateful world. In the same address, she returned to the controversy that had followed the band throughout the week, acknowledging the violent language she used while calling out a fan during Garbage’s Good Things Festival performance in Melbourne.

“I did say that I wanted to punch that guy in the face,” Manson told the crowd. “I did say that. I didn’t. And that is the difference.”

Manson addressed the issue during the show, as captured in audience-shot video.

It was a moment that clarified why the incident had refused to fade.

From the outset, the discomfort surrounding the Good Things exchange was never about whether Shirley Manson physically harmed anyone. It was about the point at which frustration crossed into violent language on a festival stage, in front of thousands of people.

During that exchange, Manson did not only speak about punching the fan herself. She also referenced the possibility of involving the crowd or her crew, prompting visible concern from security and later leading the man involved to say he feared someone in the audience might act on what was being said.

For many fans, that context mattered more than intent.

The line they expected Manson to draw was not between acting on violence and holding back. It was between using violent language at all and rejecting it outright, especially when speaking from a position of authority to a large crowd.

That expectation was shaped by Manson’s own public identity. For decades, she has spoken openly against violence, hate and injustice. Fans wanted to support that message. What unsettled them was seeing violent language defended on the basis that it was not acted upon.

The Opera House comments marked the fourth time Manson had addressed the beach ball incident in public.

The first came immediately after the Melbourne show, when she doubled down online and said she would make “no apologies.”

The second came in Brisbane, where she framed the backlash as disproportionate, referenced global suffering and questioned why people cared more about a beach ball than violence elsewhere in the world.

The third came days later in Melbourne, when she apologised for losing her cool, but added that she had never spoken to a fan like that before, except once when someone spat on her.

Now, at the Opera House, she explicitly acknowledged the violent language again, but framed the issue as a distinction between words and action.

For many fans, that framing missed the point entirely.

It suggested that violent rhetoric is acceptable so long as it does not result in physical violence, a position that sits uneasily alongside calls to reject hatred and harm. On a festival stage, in front of thousands, that distinction feels especially warped. The risk is not only what the artist does, but what someone in the crowd might do after being given permission, even implicitly, to escalate. Placed against the reality of a mass shooting hours earlier, the comparison only heightened that discomfort for some fans.

What people were waiting to hear was simpler.

Not a comparison.

Not a defence.

Not a distinction.

Just a clear statement that calling for violence from a stage is wrong, regardless of whether it is acted on.

That sentence never came.

This is why the story lingered beyond the festival, beyond the apologies, and beyond the tour itself. The backlash was not driven by bad-faith actors alone. It persisted because ordinary music fans felt a moral inconsistency they could not reconcile.

Shirley Manson has spoken openly about surviving misogyny, abuse and a brutal industry. Few fans doubt the legitimacy of her anger, or her right to make mistakes. Forgiveness was always available.

What never arrived was a clear rejection of violent language itself.

Garbage went on to complete their Opera House set, acknowledging the Bondi tragedy again before ‘Queer’ and closing the night without further comment. The show marked the final date of the band’s Australian and New Zealand tour.

As the tour ends, the beach ball incident will eventually fade from headlines. But the question it raised remains one many fans believe still matters.

Where does the line sit between anger and violence, and who is responsible for holding it when thousands of people are listening?

Garbage — Sydney Opera House Setlist (Tour Finale)

- There’s No Future in Optimism

- Hold

- I Think I’m Paranoid

- Vow

- Run Baby Run

- The Trick Is to Keep Breathing

(preceded by Shirley Manson thanking Frontier Touring, the band’s crew and the late Michael Gudinski) - Fix Me Now

(impromptu inclusion, only performance on the Australian tour) - Hammering in My Head

- Wolves

- #1 Crush

- Wicked Ways

(with a snippet of ‘Personal Jesus’ by Depeche Mode) - Queer

(preceded by acknowledgement of the Bondi shooting earlier in the day) - Chinese Fire Horse

- When I Grow Up

- Cherry Lips (Go Baby Go!)

- Push It

- The Day That I Met God

Encore:

Stupid Girl

(preceded by band introductions)

Only Happy When It Rains