Denied Batman and The Shadow, the Evil Dead director Frankensteined together his own gothic superhero.

Hey gang – Trav here. this week marks the 35th anniversary of Sam Raimi’s Darkman, a fact worth celebrating, and I happened to have an old, unpublished essay sitting in my hard drive, waiting to be unleashed upon the world like a disfigured scientist with anger management issues. Enjoy – it’s a long one.

I actually started writing this when Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness was released last year, because I’ll always use a director’s new film to shine a light on one of their old bangers if the opportunity presents itself, but life got in the way. Sam Raimi is one of the fathers of the modern Cinematic Superhero Age thanks to his work on the OG Spider-Man trilogy, but his roots in the genre go deeper than that, so let’s eschew the Marvel Universe for a minute and dig into his earlier masterpiece: the weird, lusty, OTT, pulp-inflected, horror-adjacent Darkman.

Darkman loses points for a certain audience – and gains more for others – for not being tied to an extant property. Rather, the character was willed into being after Raimi got given short shrift when he made inquiries about certain other lurid licenses that might be up for grabs for a game filmmaker with plenty of cult appeal and an appreciation for the low arts. But both Batman and The Shadow were denied him, and so Raimi set about designing his own hero, and the world is a better place for it.

We tend to frame Darkman as a superhero film, but it draws significantly more DNA from the pulps, especially the aforementioned Shadow. Universal’s monster menagerie and its literary sources are also a clear influence – there’s a bit of Frankenstein and The Phantom of the Opera; The Hunchback of Notre Dame; Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and the various werewolf flicks derived from it; and more. It’s a real grab-bag of a film, and not all the pieces fit together perfectly once assembled. That’s partly due to the nature of the character, and partly due to the film’s long and troubled production. But perfect is boring; if Darkman were perfect, I’d probably love it less.

So, who is Darkman, as the posters asked when this thing was about to hit cinemas in 1990? He’s mild-mannered scientist Dr Peyton Westlake (Liam Neeson), whose research involves artificial skin for burns victims, but when we meet him the fantastical filler dissolves after being exposed to daylight for 99 minutes. In a winning stroke of dramatic irony, he winds up needing the stuff himself after his lab is bombed and his face more or less planed down to the bone.

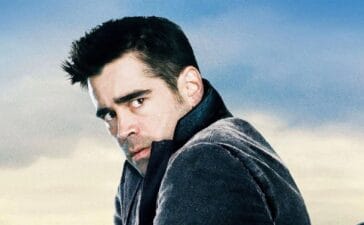

It’s not his fault. His girlfriend, Assistant District Attorney Julie Hastings (Frances McDormand) left a document there that could incriminate corrupt property developer Louis Strack (Australian actor Colin Friels in a rare US role), and so he puts his formidable henchman, organised crime boss Robert G. Durant (Larry Drake, then best known for playing a lovable mentally disabled man on L.A. Law). Durant, a man fond of collecting fingers with a cigar cutter, blows the joint up.

But it’d be a short film if Westlake didn’t survive. He’s left legally dead, his face obliterated, his nerve endings severed to control the incredible pain from his burns. His body is now possessed of superhuman strength thanks to the unchecked adrenaline now coursing through his system, and his mind wracked with psychosis as it leeches all the emotional stimulation it can get now that his body can’t feel anything. As an aside, Raimi’s brother Ivan, a doctor, worked on the script to ensure the medical science was as accurate as possible. If that’s the case, I’d love to look at what kind of shape the draft was in before he got his hands on it.

Still, when you’re a legally dead genius with super strength, high-tech artificial skin that lets you flawlessly disguise yourself as others, and a burning thirst for revenge, the way forward seems obvious. Our man sets up shop in a cathedral-like disused industrial space, starts cooking up a batch of skin, and begins planning his payback, pausing long enough to swathe himself in a fetching hat and cloak combo, because style matters.

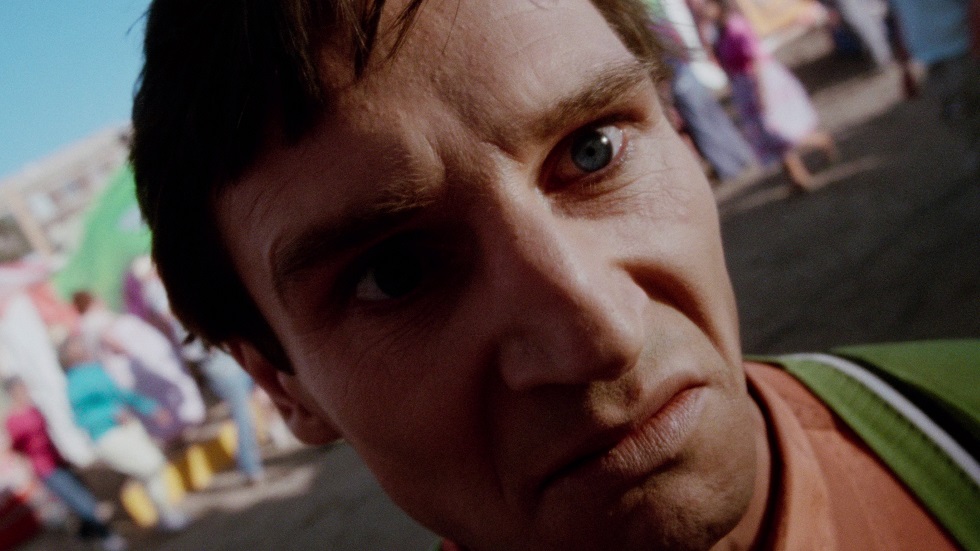

Style certainly matters to Raimi. On his fourth professional film here, Raimi’s visual aesthetic really comes into its own with Darkman, the director being handed what was, to him, a huge budget to realise his vision ($14m bought a lot more 34 years ago). Flourishes born out of micro-budget necessity on The Evil Dead really pop when underpinned by studio money. While you can certainly argue that full synthesis was achieved over a decade later when Raimi’s sensibilities made 2002’s Spider-Man pretty much a live action comic book, here there’s a tension between the two that yields remarkable results, with Raimi’s flighty, freaky imagination pulling in one direction, and the big machine of studio production in another – somewhere in the middle, there’s magic. The kind of magic where our point-of-view camera goes right in through Neeson’s eye to show us his mind aflame as a snide carnie worker pisses him off while Danny Elfman’s deranged oom-pah-pah score cranks up. Given he’s also trying to explain why he’s still alive to Dormand’s Julie, the man is under considerable pressure.

Neeson, who has always had a great – if weird and self-deprecating – sense of humour, is fantastic here, demonstrating a fearless commitment to the bit. Darkman wasn’t quite Neeson’s first leading role – that was the little-seen, rather grim social/religious drama Lamb, released in 1984. Neeson had chalked up a few high-profile supporting roles in the interim, appearing opposite Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons in The Mission (1986) and Patrick Swayze in Next of Kin (1990). In a few years he’d get a Best Actor nomination for Schindler’s List (1993) but at this point in his career you can see him trying to figure out what kind of roles work for him, and the industry figuring out how to best use him. He’s a jobbing actor game for anything, which is why you get the odd sight (retrospectively speaking) of him as a boozy club manager in the girl band misfire Satisfaction (1987) or as a narcissistic music video director in the final Dirty Harry flick, The Dead Pool (1988).

He doesn’t work in those roles, and the secret to his turn in Darkman is that he doesn’t quite work here. He’s a huge dude, a craggy-handsome working-class guy from Ballymena who has never successfully masked his Northern Ireland accent, and it’s faintly ludicrous to see him playing a bookish, brilliant scientist. But any doubts vanish when he makes the switch from poor Peyton Westlake to the demonic Darkman.

Raimi’s gift when it comes to this kind of material is that he embraces the silliness – he doesn’t try to bury the essentially juvenile elements in layers of faux-realism (I like the Dark Knight Trilogy as much as anyone, but it did some damage). Under Raimi’s direction, Neeson does the same, giving us a campy-gothic tragic hero by leaning into the melodrama. It’s interesting to imagine what Raimi’s original choice, Bruce Campbell (of course, and he gets a cameo) might have done with the role. But whatever his talents, Campbell never had the career that Neeson did, and there’s something about seeing this lauded actor hamming it up in this kind of pulp – it’s a unique flavour (Neeson’s late-career movie into low-budget action only adds piquancy).

As his opposite number we have Larry Drake, a character actor who rarely headlined but always impressed. Outside of his 143-episode run on L.A. Law, the most high-profile role of his 35-year career was as the titular killer in the half-decent 1992 slasher, Dr. Giggles. Here, he brings some twisted pre-Code gangster energy to Darkman – a little Little Caesar (1931) if you will. Raimi is on record as saying he cast Drake because he reminded him of Edward G. Robinson: “He looked so mean, so domineering, yet he had this urban wit about him. I thought, ‘My God, this guy is not only threatening-looking, he has a good physical presence – what a perfect adversary for the Darkman!’”

We actually meet Drake’s Durant and his gleefully evil gang of henchmen (a very ‘80s conceit – bad guys used to loooooove being bad) before anyone else with a fun little action sequence where they wipe out an opposing gang in a warehouse shootout. At one point one of Durant’s guys, Skip (Dan Hacks), whips out a submachinegun concealed in his artificial leg – an early indicator of the kind of cheerful, grotesque anarchy we’re in for. While Raimi spends the film building the Darkman character – it’s an origin story, after all – he gives us everything about Durant very quickly. He’s unflappable, fastidious, sadistic, and possibly queer (there’s certainly a queer reading to be made of Durant’s relationship with underling Rick, played by Ted “Sam’s brother” Raimi). He’s an iconic villain, ripped straight from an early Dick Tracy strip, and Drake, who passed in 2016, eats up the role.

Friels and McDormand fare less well, but that’s down to the material. McDormand is shackled to a pretty rote damsel-in-distress role, while Friels brings some smug, moustache-twirling vim to his role as he gets to romance the grieving Julie while Drake’s Durant provides a more direct threat. That is, up until the end when Strack’s villainy is revealed and we get a climax at a high-rise construction site that vibes strongly with the previous year’s Batman and its cathedral finale. Both McDormand and Friels feel kind of abandoned by the plot, as though much of what they’re given to do is left over from previous drafts and not strongly connected to the story at hand.

It’s unsurprising; Darkman went through a pre-production period that was both torturous and tortuous, with countless drafts being written. Sam Raimi initially turned his idea into a short story, then a treatment, after which it was passed to ex-Navy SEAL Chuck Pfarrer (who, unfortunately, wrote Navy SEALS – but also Hard Target, so all is forgiven), with subsequent drafts by Sam and Ivan, producer Robert Tapert, and Daniel and Joshua Goldin. The final script is credited to the Goldins, the Raimis, and Pfarrer.

But then add in post-production woes that included disastrous test screenings and clashes over the edit, with one editor apparently having a mental health crisis and quitting (there are two credited editors, Bud S. Smith and David Stiven, and while I can’t find any data on who bailed, Smith, as a veteran William Friedkin collaborator, is probably no stranger to stressful work environments). The resulting film is lean 96 minutes, but it’s a bit rough, a bit jumbled. One villain, the aforementioned Skippy, simply disappears from the story at one point, never to be seen again (a deleted scene has Darkman beating him to death with his artificial leg).

But what does work is wonderful, Veteran cinematographer Bill Pope was a noob here – it’s his first feature film! – but draws out all the dark beauty and guignol grandeur. The action and violence is refreshingly gruesome. Not in a cruel manner, mind you, but in a kind of EC Comics vibe. Our hero’s a nemesis, an agent of righteous retribution. He revels in his cackling revenge, at one point thrusting Ted Raimi’s Rick up through an open manhole to be squished like cantaloupe by traffic.

But he’s also a monster. How he could he not be? I’m reminded of the cover to The Incredible Hulk #1, which breathlessly asked us in the standard Marvel huckster style to contemplate, “Is he man or monster or… is he both?” He’s both, and there’s no living with other people in his state. Which is his choice at the film’s denouement to walk away from Julie is so perfect and resonant. Apparently test audiences complained about the lack of happy ending, but what other ending could possibly suit this pulp-gothic tragedy? And, you know, for the franchise-minded, it sets us up perfectly for The Further Adventures of…

Which we got! In dribs and drabs. Darkman was a soft box-office success, but the home video boom saw two TV movie sequels shot back-to-back in Vancouver on a shoestring budget, with main mummy Arnold Vosloo subbing in for Neeson. They’re decent enough. Not brilliant, and certainly artefacts of that period in TV, but director Bradford May does a lot with a little, milking his meagre funds for all the production value he can, including what was at the time the biggest practical explosion in Canadian film history for Darkman III: Die Darkman Die (1996) That instalment also boasts a villainous turn from a scenery-chewing Jeff Fahey, who knew exactly what the role required. The previous film, Darkman II: The Return of Durant (1995) gets us Larry Drake again, but the third edges it in terms of simple fun.

A television pilot was shot and quickly torpedoed circa 1992, and we got a quartet of sequel novels by Randall Boyll in 1994, plus a short-lived Marvel comics series written by Kurt Busiek, and a later appearance in a Boom! Studios Ash comic. There’s always at least a little interest in doing something with the property, and even Sam Raimi himself made some rumblings to that effect in a recent interview.

But I don’t know about that; it might be a mistake to resurrect this one. Some films are lightning in a bottle, and their flaws are part of the alchemy. You could, I suppose, make an “objectively” good or even better continuation, but you won’t recapture the magic of the original, which is some uncanny, fragile thing we were just lucky wound up in front of camera (it occurs to me that this is the essential problem with the entire Ghostbusters franchise). In this age of IP filmmaking, taking a sander to Darkman’s rough edges might make it a more palatable product, but it’d almost certainly expunge what makes it special.