“Walk down the right back alley in Sin City and you can find anything.”

It’s been 15 years since maverick director Robert Rodriguez brought Frank Miller’s Sin City comics to the big screen for the first time. A mostly monochrome noir pastiche packed with heavy, albeit cartoonish, violence, the film adapted four of the comic book storylines, presenting audiences with a rain-drenched, neon-lit urban world populated with terminally tough guys, serpentine and sexy dames, grotesque villains, corrupt cops, and more, all working an angle and trying to get ahead in the titular Big Bad Town.

The wrinkle is that Rodriguez, a wunderkind whose early low budget films like El Mariachi (1992) and Desperado (1995) had given him both the taste and the talent for technical innovation on limited resources, didn’t want to make Miller’s striking comics – grim, impressionistic street poems filled with bold, atmospheric splash pages interspersed with terse scenes of tough, Mickey Spillane-inflected dialogue and no shortage of kinky cheesecake shots – conform to the tenets of cinema, but the other way around. The future Alita: Battle Angel director aimed to make the film as close to the original comics as possible, down to recreating individual panels as moving images. Miller, who had knocked back numerous Hollywood offers in the past, was convinced when Rodriguez showed him some test footage he’d whipped up in his home studio, and then invited him to witness an additional test shoot which eventually evolved into the film’s actual opening scene.

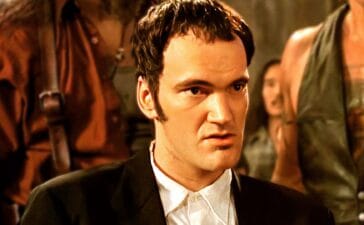

“This is also the film that saw Quentin Tarantino dabble (for what appears to be the only time on record) in digital filmmaking…”

When Sin City first hit cinemas in April of 2005, the film landscape was a very different space. We were three years shy of the big comic book adaptation (well, really, superhero) book, which really kicked into gear with the triumphant Hail Mary pass that was Marvel’s Iron Man. Hell, we were still a month shy of Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, which a) was ground zero for modern “serious” takes on pulpy comic book fare, and b) deeply influenced by cartoonist Frank Miller’s work on Batman. But importantly, CGI hadn’t become the ubiquitous go-to filmmaking tool it is now, with elaborate sets and practical and optical effects still being the norm for big budget cinema, although computer imagery had been making steady inroads into the effects field for a decade or two. To best recreate Miller’s on-page world, Rodriguez planned to shoot his actors against green screens, with limited sets and physical props, painting in the backgrounds later. The previous year’s Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow had tried something similar, but had crashed and burned at the box office, but Rodriguez, who to this day espouses technical mastery as a key way to overcome budgetary limitations, was confident he could pull it off.

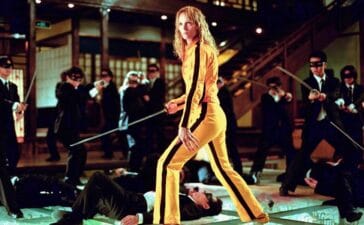

That confidence proved infectious, with a truly impressive cast rallying to Rodriguez and Miller’s flag, chief among them Mickey Rourke as Marv, the series iconic antihero, a Frankenstein-looking bruiser in a trench coat who tears the town apart after his lover is murdered. Bruce Willis, then still actually engaged with his career, took on the role of Hartigan, the only honest cop in Sin City, who sacrifices his reputation, his honour, and ultimately his life to protect kidnap victim Nancy Callahan (Jessica Alba). Clive Owen turns up as Dwight, two-fisted gunfighter who tries to head off a war between the prostitutes of Old Town, led by “Valkyrie” Gail (Rosario Dawson) and Mob Boss Wallenquist (Sir Not Appearing In This Film, but represented by the late Michael Clarke Duncan’s hulking enforcer, Manute) after the murder of corrupt cop Jackie Boy (Benicio Del Toro).

And that’s just the starting line-up. Elijah Wood shows up as a taciturn cannibal, Rutger Hauer a venal priest (and Frank Miller himself as another venal priest), Power Boothe a corrupt politician, Josh Hartnett a hitman, Nick Stahl a freakish, yellow-skinned pervert. Then there’s Carla Gugino, Michael Madsen, Brittany Murphy, Devon Aoki, Tommy Flanagan, even an early appearance by the beloved Nick Offerman – all happy to be slathered in prosthetic make-up or squeezed into skintight latex and shot in near-monochrome to best recreate Miller’s magazine milieu (the odd splash of signature colour aside, the film is black and white).

“It’s so close to the source material that Rodriguez gave Miller, who was present on set, a co-directing credit, which was against DGA rules; Rodriguez simply quit the Guild…”

It was, by any measure, a bold stylistic and technical experiment, the results of which manifested on screen in a variety of ways. Famously, Rourke and Wood never actually worked together on set; the fight scene between their two characters was shot with each actor on different days and cut together digitally later – a now fairly common approach which was at the time quite revolutionary. This is also the film that saw Quentin Tarantino dabble (for what appears to be the only time on record) in digital filmmaking, with old mate Rodriguez inviting the Once Upon a Time in Hollywood helmer to guest direct a sequence just so he could see how the technology handled. It didn’t stick, with Tarantino preferring film stock to this day, but the scene, in which Owen’s Dwight has an imaginary conversation with Jackie Boy’s severed head, is a banger.

And it’s an experiment that paid off. Sin City is a singular film; a sleek, hyper-stylised slice of comic book noir that captures Miller’s original books with an accuracy and, importantly, an artistic fidelity that no other comic book movie has come close to. it’s so close to the source material that Rodriguez gave Miller, who was present on set, a co-directing credit, which was against DGA rules; Rodriguez simply quit the Guild and Miller got his credit – the film is properly titled Frank Miller’s Sin City for a reason.

The movie is not just the essence of the books writ large, but the books brought to life; Rourke’s Marv, covered in stark white band-aids and muttering tough guy lines as he kills his way up the chain of command to find his nemesis, is the comic book character in motion. Owen may not be an exact likeness for Dwight, but when he’s jumping down a manhole with both pistols blazing, it’s a perfect kinetic representation of Miller’s visual style. The dialogue is on the nose at times, with each line calibrated for maximum macho posturing and/or sexual innuendo, but to complain about that is to not see the forest for the trees – the pastiche is the point, and playing the hard-boiled zingers straight-faced is part of the charm.

Some elements, it must be said, have not aged as well. Are the girls of Old Town, a coterie of deadly sex workers who can kill anyone who crosses them but still walk the streets, sex-positive feminism in action or prurient post-adolescent fantasies made flesh? The jury is out, perhaps, but the latter seems more likely. Nancy’s love for Hartigan, a man decades older than her that she first met when she was 10, reads creepier by the year. The odd spot of casual homophobic dialogue lands with a thud to modern ears.

But Sin City is a film – an entire property, really – of moments; big, iconic beats that resonate in both the genre and the gut, and it’s easy enough to tune out those discrete moments that don’t fly for the individual viewer. Much more difficult, though, is replicating the success of Rodriguez and Miller’s film, as their failure to do so with the long-delayed and much-maligned Sin City: A Dame to Kill For in 2014 demonstrates. We’re supposed to be getting an anthology-style TV series in the not too distant future, and while the format might suit the source material, the safe bet is that, as a film, 2005’s Sin City is a one off – a beautiful, brutal, blood-slick urban fairytale of bullets, broads and booze.