Filmmaker Julien Temple has set himself up as the pre-eminent cinematic chronicler of post-war British counterculture. He made not one but three films about The Sex Pistols.

He made the definitive documentary on the life of Joe Strummer. He fictionalised and mythologised the arrival of rock ‘n’ roll in England with Absolute Beginners, lionised both Ray and Dave Davies, and set the record straight on Britain’s most famous music festival with the 2006 doco, Glastonbury. Add in music videos for pretty much everyone, and it’s not a bad résumé.

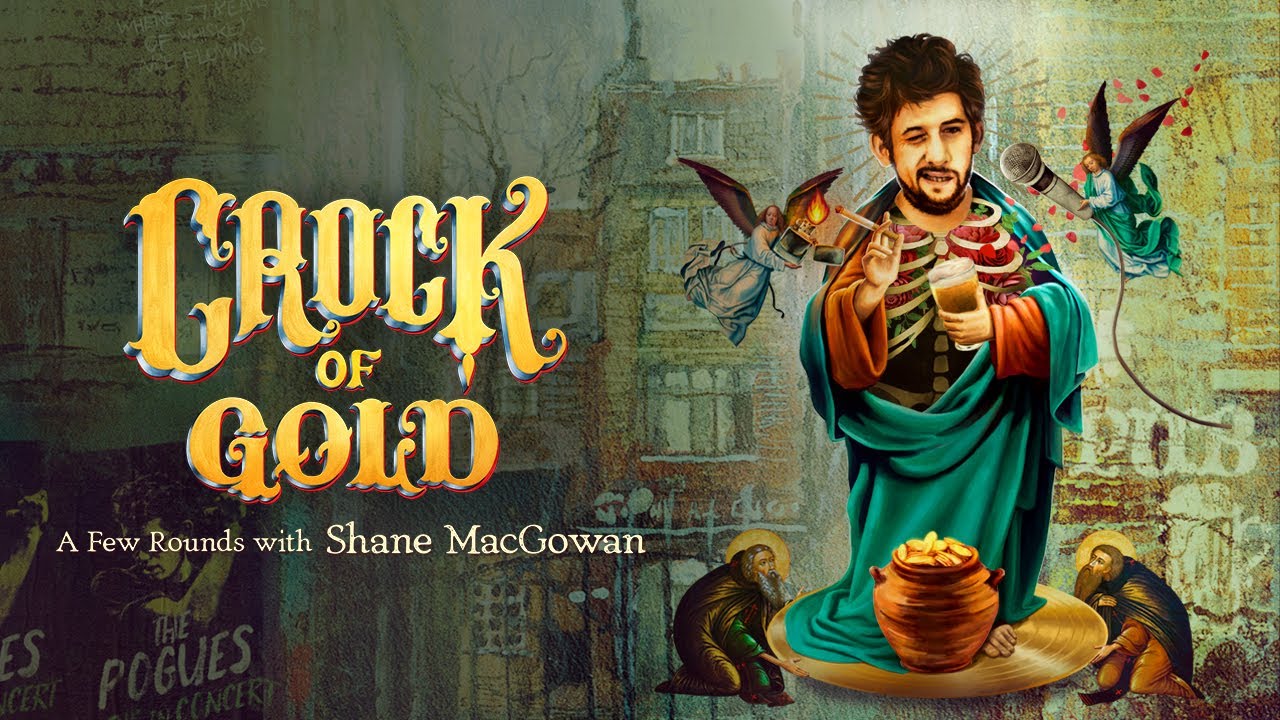

But Temple’s most difficult project was his latest: Crock of Gold – A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan, a look at the life and career of the legendary Pogues frontman. As famous for his belligerence and boozing as his sublime songwriting, MacGowan balked at a conventional documentary, so what we get instead is a series of conversations between the rotten-toothed raconteur and the likes of Johnny Depp (who also produces), Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie, and even former Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams, with animation and archival footage rounding out the story.

This is an extraordinary film of real depth and lyricism which simultaneously lauds its controversial subject and makes no bones about the sorry state his alcoholism has left him in. So, we simply have to ask: how did all this come about?

Well, my cameraman friend, Steve Organ, who I shoot a lot of films with, just asked me one day whether I’d be up for doing a film about Shane. He knows this guy who runs a pub called The Boogaloo in London, a kind of music pub where Shane used to stay at. He also knew a guy who kind of unofficially manages Shane, a guy called Gerry O’Boyle: he was putting it together and I said, “Well, I’ll meet them.” So, I went to meet Gerry and Shane and they asked me if I would do it.

I wasn’t sure, you know: he comes with a reputation, obviously, of not being the most easy guy in the world. I was also finishing another film, so I couldn’t do what they wanted me to do immediately. I didn’t think much more about it, but then Johnny Depp called me and said he was hoping to get it going and would I get involved.

In a way that made the difference, because I knew I had a guy who would have my back and help make sure the film had a good chance of being finished. Yeah, it was Johnny who tipped the scales. I’ve known Johnny a long time, as has Shane.

And you’ve known Shane for a long time as well, right? You first bumped into him back in the punk scene in the ‘70s, if I’m correct.

Yeah, that’s right. That’s when I first was aware of him and met him and I did the first interview that he ever did, which is in the film, where he talks about sniffing glue and he’s got the peroxide blonde hair out of the bottle that you had to have to become a punk at the beginning. A kind of Marlon Brando, Julius Caesar look, which didn’t last long, that phase, but everyone seemed to go through it. I remember Joe [Strummer] putting too much on, way too much.

I understand Shane was happy to do the documentary, but he didn’t want to be interviewed. So how did you negotiate that difficulty?

It was difficult. Even if you don’t use an interview, at least you can hang things off it and start shaping something, but it did things that were good for the film. It sent us off on this mad search for micro cassette recordings in journalists’ attics from the mid ‘80s in Bratislava or wherever they played in some bar at five in the morning where he’d be spilling words of wisdom. We found things that you wouldn’t get from a sit-down wrinkly, ‘old rock star in an armchair’ type event. And he was a much better storyteller back then actually; he could string pretty amazing sentences together, which is not so easy for him now. In a way it was better; it forced us to go to the source and get all these different versions of the same stories, which was fun.

But the problem was, if we do want him saying some things, can we even get him to do that in conversation? I prepped Johnny with all these questions I wanted to weave into the conversation and then we sat filming them for eight hours and I was like, “Johnny, where’s the questions?” They were talking about Kris Kristofferson for a couple of hours and I was like, Jesus, it’s not a film about Kris Kristofferson, you know?

But the good thing about those filmed conversations is you get different versions of Shane. He’s very different with Johnny Depp and very different again with Gerry Adams. I’ve never seen him look up to someone like that; there’s a kind of reverence there that’s rare, I think. And then he reverts to type with Bobby Gillespie. So you’ve got a range of different Shanes, which is really what the movie is about. These different versions of Shane and different versions of who he is and how he concocted myths and fairy tales about himself to create this extraordinary persona. The fact that he was difficult was really quite key in pushing us into doing things that made the film more interesting.

What I found really interesting about the film apart from Shane and his whole story is that it’s also kind of a social documentary. It deals a lot with the history of Ireland the way your film London: The Modern Babylon dealt with the history of that city. How did that emerge?

I wasn’t that well-versed in Shane’s childhood. I didn’t really know where he had grown up. I thought he was from London, but he did spend a lot of time in this extraordinary unchanged bit of Ireland, probably one of the last children to see the really old Ireland that hadn’t changed since the 18th century with no water, no electricity – just donkeys and carts. He has a very powerful connection to that; I didn’t realise that strongness, that sense of Irishness, was so interwoven into who he is. I learned that and through learning that I learned more about the history, and it was exciting to tell a bit of the story through his eyes, of England and Ireland, that kids in England really aren’t taught at school. They just don’t go there because it’s too nasty a story.

So yeah, it was interesting to do that, and also to look at the London Irish culture and the effect that Shane had on that, giving that community a voice for the first time.

You know, one of the best things about doing these films is you are learning about stuff you don’t know, and in quite a deep and meaningful way, it’s like being at university again in a way. I’m not so interested in films just about music or technique or guys sitting at a mixing desk saying which engineer recorded their album – that’s not what I’m into. It’s more using the music as a window into the people who made it, the audiences who made it popular, and the place and the time and where they came from and what fed into what they were feeling. They’re all kind of social histories really, as much as anything else, and a form of time travel as well, I hope.

I enjoy that sense that music and moving images from another time can really… it’s the closest to get to being there, I think, that combination of those two things – the abstract feeling of being there with the music and the more specific feeling of the images – is really interesting. They can pull apart at times, but also come together. It’s a nice thing to play with.

What’s striking about Crock of Gold is that there’s a sense of celebration and majesty to it because of Shane’s music, his achievements and his position in arts culture. But also, he’s a bit of a wreck from the drinking. How do you, as a filmmaker, approach that?

I like the sense that it’s a very funny film at times and there’s a very up feeling in some of the gigs, but then it’s quite a hard watch at other times. I like the tension of that. It can turn on a sixpence a little bit, quickly reversing the feeling that you were in. I think it was just a question of showing what’s really there with Shane. It’s a range of things: it’s a triumph on one level and a tragedy on another level. But it is also about how far he was prepared to go to bring back these songs from some pit of hell that he would regularly frequent. It’s a strange film about creativity; his creativity and where it came from and how he how he stoked it.

But I hate pundit films where people tell you what to think about someone, all talking heads telling you what to think. It’s better to let the guy himself do what he does and say what he says. I’m trying to show that from as many different perspectives on who he is and then let the audience just make up their own mind. Just set it out there, not casting judgement or having other people cast judgement. I think it’s a rich cocktail of emotions you go through, but that’s Shane. There is something really generous and lovable about him and there’s something genuinely abusive and really off-putting and dislikeable about him too. It’s strange; you don’t know what you’re going to get, basically.

There are a couple of opposing theories on substance abuse and creativity. One is that some of the greats are great in spite of their consumption, and the other theory is that they are great because of their consumption – that the boozing and the drugs is integral to their creative process. Where do you think Shane fits in on that spectrum?

I don’t know. Coleridge, for example, was a person who had such an explosive mind that he had to tie lead weights around it with laudanum to stop it flying away. I think that’s a reason that people do certain substances, but not necessarily in Shane’s case. I think alcohol made him bolder. I think he’s shy, and I think a lot of people drink to get over shyness, you know? I think he could inhabit this swaggering persona of Shane MacGowan more easily when he had a few drinks, and that he had to be in that space to write these songs, so I think they are linked in a way. I certainly know a lot of people that don’t need to get off their heads to write interesting things, but I have nothing against whatever way people choose to access that inner thing that they need to reach to be creative on that level. I mean, he’s a brilliant lyricist and songwriter. There’s no doubt about it. I think he’s written some amazing songs. He’s been very fucked up for the last 15 years and hasn’t written any songs, but he was pretty fucked up the previous 15 years and then wrote a lot of good songs. So, I don’t know what that proves. What do you think?

It’s interesting. I really liked the film and I cried at a couple points, but I think the point which made me the saddest was when he was lamenting to Johnny that he’d like to write some more songs and he clearly hasn’t written in quite some time. He was this incredible creative firebrand and the question is well, wait, where’s the fire now, man?

I know. It’s sad to see it almost out, isn’t it? It was a difficult film for me to make, I almost walked off I don’t know how many times because the abuse is tough to take. But then you learn to roll with it and there’s this thing in him that’s lovable too, you know? You don’t just go ,”Oh, I never want to see him again.” You do care about him and you do like him. There’s something on one level really honest about him and on other levels there’s deceit there as well. It’s a cocktail of fantastic contradictions, really, and I think the contradictions in a way make people great.