What started as a strange, funny festival moment became one of the most unexpected cultural flashpoints of the Australian music year.

A beach ball.

A frontwoman losing her temper.

A fan singled out in front of tens of thousands.

And then something bigger.

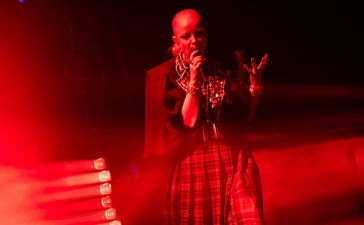

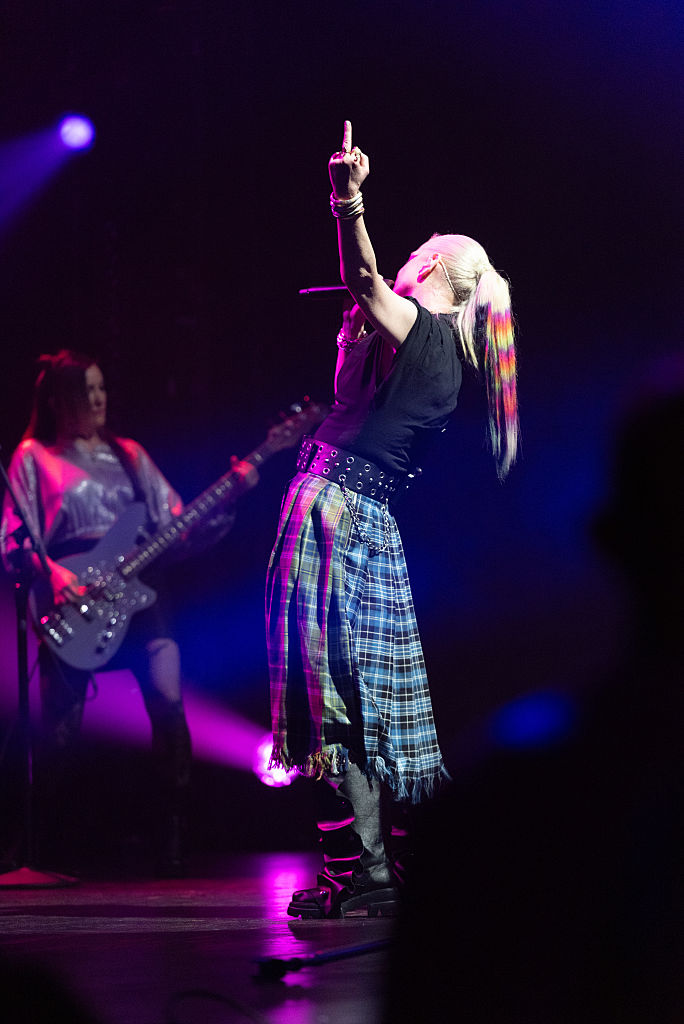

Over the past week, the fallout from Shirley Manson’s on-stage outburst at Good Things Melbourne has grown far beyond the festival itself, eclipsing lineups, sets and even the tour that surrounded it. Across BLUNT’s platforms alone, the story helped drive more than 20 million views in three days, cutting across fan communities, political divides and online subcultures that rarely agree on anything.

Now, days later, Manson has offered a third attempt at addressing what happened. This time it came as a quieter, more personal apology delivered on stage in Melbourne on Thursday night. The question fans are now asking is simple.

Does this one finally land?

From Good Things to Global: How a Beach Ball Became the Story of the Tour

To understand why this apology matters, you have to rewind to how the moment first landed.

In the early moments, it played like sharp, uncomfortable stage banter. But when the language tipped toward violence, the mood in the crowd shifted and the room went quiet.

The moment was filmed. The language around violence stuck. And within hours, it was everywhere.

What followed mattered just as much as what happened on stage.

That same night, Manson doubled down publicly, posting that she would make “NO APOLOGIES” for calling out beach balls at shows. Two days later in Brisbane, she addressed the controversy again, joking about being labelled the “motherf***ing antichrist,” delivering a sarcastic apology to “blessed beach balls,” and pivoting to global issues like Palestine and the exploitation of musicians.

That Brisbane moment did not cool things down. If anything, it hardened the divide.

Then, just yesterday, another apology surfaced. This time it came from Melbourne, delivered six days after the original incident and four days after Brisbane. The video only began circulating widely on Friday afternoon.

This time, the tone was different.

The Melbourne Reset: The Apology That Arrived Six Days Later

On stage in Melbourne, Manson told the crowd:

“If that person was indeed who they said he was, and he was a Garbage fan, then I would’ve never spoken to him the way I did.

I would like you to bear in mind that everything is contextual. If you’re not given any context then you have no idea what went on.

I’ve had a thirty-year career. I have never spoken to any fan like that in my life before except one time, when one c**t spat on me once.

Thank you to the fakes, thank you to the true fans. We love you. I’m sorry I lost my cool. But I still f***ing hate beach balls, and I always will.”

Compared to Brisbane, this was undeniably more human. For the first time, Manson clearly acknowledged losing her cool and framed the moment as an exception rather than a principle.

But even now, fans are debating whether it resolves the issue or simply reframes it.

Why This Apology Hit Different This Time

By the time this apology arrived, the story had already evolved.

Reporting, including BLUNT’s interview with the man involved, had clarified that he was a lifelong Garbage fan who wasn’t causing trouble in the crowd. Rumours that he had been harassing other patrons fell apart. That context had been widely circulated for days.

In that light, the line “if that person was indeed who they said he was” reads less like uncertainty and more like a response to information that had already entered the public record.

The apology wasn’t instinctive.

It was reflective and informed.

That doesn’t make it insincere. But it does explain why it landed differently.

Why ‘No Apologies’ Broke the Fan Contract

For many fans, the initial outburst was forgivable. People misjudge moments. Stages are intense. Festivals are chaotic. Most believed that if Shirley had come out early and said, “I crossed a line, especially with the violence,” the story would have ended almost immediately.

But when she doubled down, that grace evaporated.

Not because fans wanted to cancel her, but because the double-down clashed with who she has always presented herself to be.

Shirley Manson isn’t just a singer to her audience. She’s a moral voice. Someone who speaks openly about justice, power, and opposing harm. When she framed the backlash as media hysteria, mocked the reaction, and refused to apologise while continuing to invoke global violence and humanitarian crises, fans felt a disconnect they couldn’t reconcile.

The issue wasn’t the beach ball.

It wasn’t even the anger.

It was the refusal to clearly say that threatening or invoking violence, even rhetorically, crossed a line.

That’s the line fans expected her to hold herself to, because it’s the same line she asks the world to hold itself to.

When the Algorithm Smelled Blood

It is also impossible to ignore how much this moment was amplified by opportunistic bad-faith actors online.

Once the clip crossed into manosphere territory, the outrage machine kicked into gear. For those circles, the appeal wasn’t the fan or the festival. It was the opportunity to pile onto a woman outspoken on human rights and Palestine, regardless of context or consistency. Their engagement was rewarded by the algorithm, and the reach exploded.

But that doesn’t erase the discomfort felt by fans acting in good faith.

The criticism that stuck wasn’t coming from incels or culture-war trolls. It came from people who love Garbage, who grew up with the band, and who were unsettled by the way violence entered the conversation.

Both things can be true at once.

Why Everyone Had an Opinion, Even People Who Don’t Like Garbage

This story travelled because it collided with multiple fault lines at once.

It was absurd. An adult melting down over a beach ball in Australia.

But it was also about power, identity, and expectation.

A global artist versus one fan.

Rhetoric about justice colliding with a moment of aggression.

A figure who has spent decades speaking about harm now perceived to be minimising it.

For one rare moment online, groups that almost never align found themselves sharing the same unease.

That’s why this didn’t burn out in 24 hours.

Opera House Tomorrow: The Last Show of the AU/NZ Run

There is one more layer that gives this moment its emotional charge.

Manson has been open throughout the band’s recent world tour about the toll of touring and the reality that long-haul international runs like this may not continue forever under the current industry model. Garbage close out their Australian and New Zealand run at the Sydney Opera House tomorrow night, the final show of this leg.

For some fans, it is hard not to see the Opera House as a fitting venue for where Shirley Manson is now. Older. Sharper. Less tolerant of chaos. Less interested in circus energy. More interested in control.

If this does turn out to be the band’s last Australian tour, the weight of this week feels heavier. Not as a defining scandal, but as a reminder of how quickly small moments can become symbolic ones at the end of an era.

Does This Actually Close It, Or Just Complicate It?

It is too early to say.

This apology is new. It is only just circulating. And it is undeniably more grounded than what came before it.

For some fans, it may be enough.

For others, the unresolved issue of violence still lingers.

What is clear is this. The backlash was never really about a beach ball. It was about consistency, accountability, and the standards we hold the people we admire to, especially when they have helped set those standards themselves.

As Garbage take the stage at the Opera House to close out the tour, this story will likely fade from the algorithm. But the lesson it exposed will not.

In the current climate, small moments do not stay small.

And humanity on stage is no longer afforded the grace it once was.