John Carpenter’s dystopian classic has lost none of its edge since in hit screens back in ’81.

If punk has a defining characteristic, it’s surely a healthy mistrust of and disrespect for authority. The simple, inescapable understanding that the people in charge probably don’t have our best interests at heart. You can build beaucoup strawmen from that basic material and plenty of them have been marching in our cities the past few weekends like the absolute bell-ends they are, but the fundamental point remains.

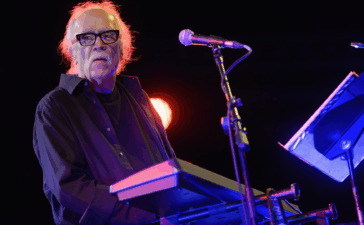

With that in mind, for my money John Carpenter remains the most punk director of all time. The call him the Master of Horror, but that’s a misnomer (though, hey – he made Halloween and The Thing, so point taken). If there’s a thematic constant to Carpenter’s body of work, it’s that the system is incompetent at best, actively malevolent at worst. The game is rigged, the dealers are in on it. Authority figures are hapless buffoons on a good day and sociopaths on the median. The best you can hope to do is carve your own path, cut yourself a little slack (in the Subgenius sense), and live another day. From Dark Star to Assault on Precinct 13, They Live and even lighter fare like Big Trouble in Little China and Starman, Carpenter has shouted this ethos, but never louder than he did in Escape From New York, released 40 years ago on July 10, 1981.

Bad Old New York in the Dark Future of 1997

“In 1988, the crime rate in the United States rises four hundred percent. The once-great city of New York becomes the one maximum security prison for the entire country. A fifty-foot containment wall is erected along the New Jersey shoreline, across the Harlem River, and down along the Brooklyn shoreline. It completely surrounds Manhattan Island. All bridges and waterways are mined. The United States Police Force, like an army, is encamped around the island. There are no guards inside the prison, only prisoners and the worlds they have made. The rules are simple: Once you go in, you don’t come out.”

The premise is sketched and quickly by the above voiceover (an audio-only cameo from Halloween star Jamie Lee Curtis) as Escape From New York begins, and then we’re plunged into the action as Airforce One goes down over the island prison of Manhattan – with the President (Donald Pleasance, because Carpenter loves his stock company) on board. He’s quickly captured by the warlord who controls Manhattan inside the walls – The Duke of New York (Isaac Hayes, never better).

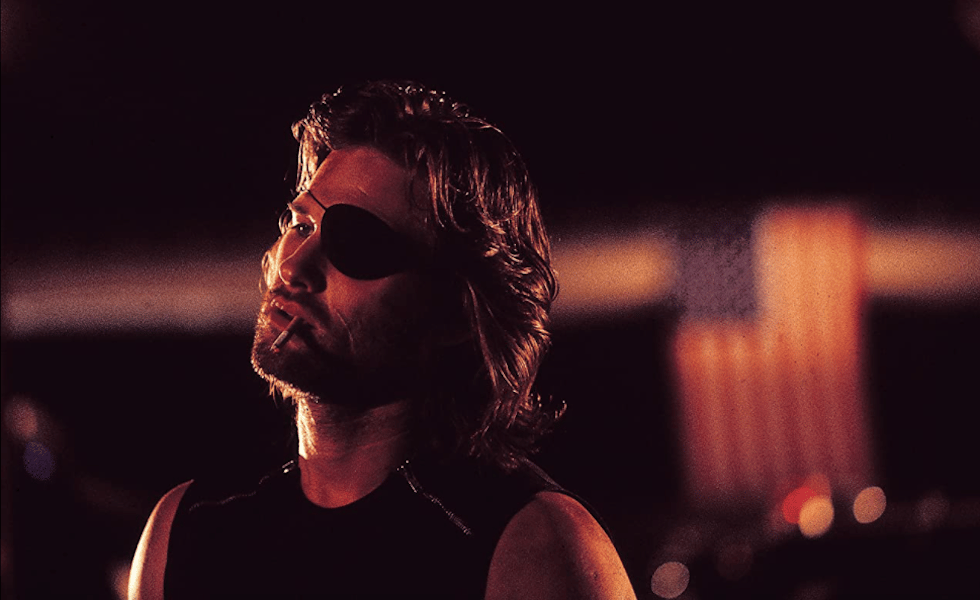

Needing the President alive for vital peace talks with China and the USSR as World War III is currently raging offscreen, Police Commissioner Bob Hauk (Lee Van Cleef, and the cast only gets better from here) hatches on a plan – pressgang former Special Forces killing machine and current outlaw legend Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell) into a one-man rescue mission. To keep him in line, they stick two microscopic bombs in his carotid arteries – if he doesn’t get the job done in 24 hours, pop go the neck pipes. And so Snake, a one-eyed, laconic, lupine killer who clearly gives zero fucks about any other human being, must fight his way through the gangs, crazies, and cannibals of New York in order to save a world he just cannot stand.

Call Me Snake

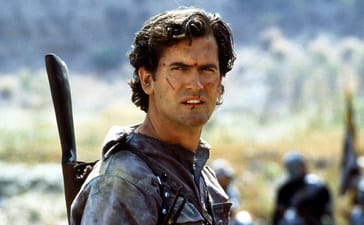

Escape From New York has a truly stacked cast of B-movie legends. In addition to the above, the great Ernest Borgnine shows up as Cabbie, a taxi driver who appears to have been living in New York since before it was walled off and drives his cab around listening to showtunes. The even greater (sorry, Ernest) Harry Dean Stanton is Brain, the Duke’s pet intellectual and an old frenemy of Snake’s. Adrienne Barbeau, then married to Carpenter, is Maggie, Brain’s squeeze. Hulking wrestler OX Baker is Slag, a goon Snake has to fight in a gladiatorial arena in Madison Square Garden.

But it’s all about Snake Plissken, one of the most iconic antiheroes in film history. The studio wanted Charles Bronson, Tommy Lee Jones, or someone with similar tough guy bona fides. Carpenter held out for Kurt Russell, who he’d just directed in the title role of the TV movie, Elvis. Now it se4ems like a no-brainer, but this was not the Kurt Russell of today; at the time he was a former child star known for a string of Disney hits like “The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes” and a short minor league baseball career that was KOed thanks to a blown rotator cuff. He was a successful actor but felt pigeon-holed and was looking for something to break out with. And then along came Escape From New York.

Make no mistake, the Russell we know today begins here. His cut down, minimalist performance owes a fair debt to Clint Eastwood’s The Man with No Name, but with an added aura of menace. Clint probably wouldn’t shoot a witness – but Snake might, if he had to. Snake’s history is largely hinted at: a sterling military career, then a notorious life of crime, with us left to wonder what happened to connect the two. That missing eye got something to do with it?

It certainly has something to with the character’s indelible mark on pop culture. With his eyepatch, his urban camo pants, the MAC-10 submachinegun he guns fools down with, he’s a striking figure on the screen, someone you just love to watch. And with his mysterious backstory, he’s to project onto – for all his martial prowess, Snake’s real superpower is his lack of fucks to give, and we’ve all wondered what we might do if we ever reach that rarefied state of Zen fucklessness.

Escape Today

Which is, I think, the key to the film’s enduring appeal, but there are other reasons. The stunning, deliciously dirty production design by Joe Alves (he built the shark in Jaws), who turned swathes of East St Louis, still derelict after a massive fire in 1976, into EFNY’s NYC. The quickly sketched, indelible worldbuilding, which lets phrases like “You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad”, as Hauk says to Snake, carry so much intriguing possibility without nailing us down to boring, fixed “truths” about Snake’s universe. The staccato electronic score by Carpenter and Alan Howarth, both futuristic and foreboding.

Watching Escape From New York today, it still stands up. It has dated somewhat, chiefly in thew pacing, which may be a little deliberate for modern action fans. Some of the effects don’t work as well as the used to, bound by the tech of the time and extrapolating ideas from then-current notions about the future. But that’s just part and parcel of watching old films.

But what works is the tone, the character, and the deeply cynical attitude towards authority of all stripes. Escape From New York remains where other dystopias have fallen because what it’s really about is a mood that is never too far from our minds: the knowledge that we’re being oppressed, suppressed, subjected to lives we don’t want to live by people who don’t really care if we do, and the tantalising possibility that once our last fuck is given we’ll be free to walk out own path – even in Manhattan Federal Penitentiary.