The fourth film in the screen-centric horror series seems more relevant than ever now that we’re all living and working online, as Travis Johnson discusses.

Now streaming on Shudder, V/H/S/94 is the latest in the anthology series that began in 2012 with, unsurprisingly, V/H/S. The franchise has earned a reputation as a proving ground and experimental space for both established and emerging horror talent, with notable directors such as Adam Wingard (You’re Next), Ti West (The Innkeepers), David Bruckner (The Night House), Timo Tjahjanto (The Night Comes For Us) and more contributing short films over the years.

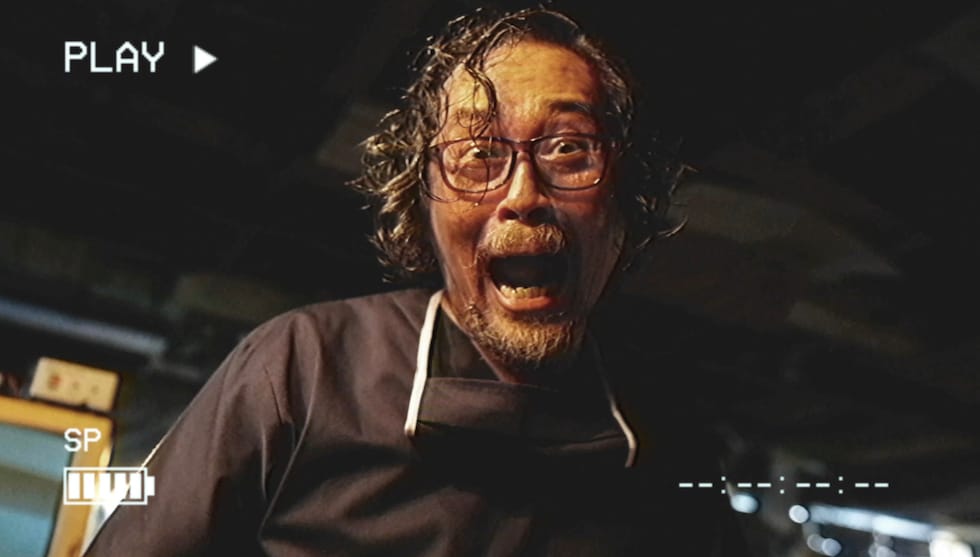

To this list we can add video artist and filmmaker Jennifer Reeder, whose segment, “Holy Hell” links the other shorts in V/H/S/94. In it, a SWAT team finds the drug lab they’re raiding is home to vast collection of VHS tapes, a discovery that sets them on a downward spiralling path to stranger and stranger horrors.

Appropriately for both These Strange Times and the whole V/H/S conceit, I caught up with Reeder for a Zoom chat about her work on V/H/S/94.

Our entire lives are mediated through screens now, which is kind of what your segment of V/H/S/94 is about. What inspired you?

I was actually kind of involved late in the game. David Bruckner, who’s been part of the, the VHS franchise for a while, was supposed to direct the wrap-around. And in the spring he got pulled off of V/H/S/94 to direct Hellraiser, which he’s doing right now. And so the producers reached out to me and asked me if I’d be interested.

I was interested in doing something from 1994; at least in the States, there’s lots of things that happened in 1994 that we know about strictly through amateur videotapes: the OJ Bronco chase and the Nancy Kerrigan knee whacking and Kurt Cobain’s funeral, the Branch Davidian fire in Waco, Texas. I came in when there were two versions of the wraparound script that had been written: one that David Bruckner had written in and one that Simon Barrett had written, both with the general idea of a SWAT team that raids what they think is a drug super lab and it turns into something else. Both their versions were just these bursts of things happening between the shorts, but I wanted to try and make the wraparound a story in itself, so it had a kind of a beginning and an end.

A week before I was brought on, I had watched David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, which I really like to watch at least once a year. I’m such a huge fan of that film. I really love it. And so, I thought, oh, this is perfect: what if this drug that’s being made in this lab is VHS tapes? That’s the drug, the signal is the salvation.

I thought that not only did it feel like it fit into the era of the mid ‘90s, but I thought that if anyone wanted to think through it further then there’s a message that is relevant to who we are as screen-addicted, signal-addicted people.

– Jennifer Reeder

Because we’ve all been in lockdown and having zoom meetings and working and socialising online, there have been a lot of conversations lately about screen time, social media, media addiction, the need for digital detox and so on. Were those things that you had in mind when you were working on the project or is it just the tenor of the times?

Even just watching Videodrome again I thought, gosh, this is such a radical film still, because we really do still live in a time when people of all ages are addicted to the signal. I mean, now it’s a digital signal, but we are addicted to the signals and addicted to screens. And oftentimes the origin of content seems like a mystery, you know? Like, who are these TikTok influencers? Where is this studio where they’re making all of these teeny tiny little videos? So I thought that not only did it feel like it fit into the era of the mid ‘90s, but I thought that if anyone wanted to think through it further then there’s a message that is relevant to who we are as screen-addicted, signal-addicted people.

I heard someone say recently the worst way to watch Videodrome is actually in a beautiful presentation on a big screen, and it should be watched on a shitty VHS tape, ideally, where you don’t quite know what you’re watching. And that kind of feeds into Marshall McLuhan’s media theories, about how in some ways the medium is the message. What formal choices did you make in your medium to communicate your message?

Well, at the very least I really wanted the space itself to be kind of buzzing with an RGB signal. I wanted there to be these light sources that were a constant red, green, blue – the colours of an analogue signal. And then I also wanted there to be as many tube TVs in the space as possible: just TVs kind of everywhere, ones that were kind of scrambled or even just a sort of blue screen or a green screen or especially ones that would have footage on there from 1994. So, without crossing any kind of copyright, we packed those TVs full of footage from 1994, but it really was about making sure that in every scene there was some kind of a television on, or if there wasn’t a television, there was this RGB signal in the space. So, it felt like every time you would come out of one of the shorts and back into that warehouse it was hypnotic. I really wanted to give you that sense of this inescapable and kind of unrelenting analogue signal.

Your background is in video art. How did you find yourself working in the horror idiom?

Every single project that I’ve done while it might not fall under a horror umbrella, I definitely think that everything that I have made kind of leans into the darker aspects of the human experience and even the more narrative shorts that I’ve done leading up to the features that I’ve made in the past couple of years featured bleeding bodies and dead bodies and people coping with trauma. There’s more narrative and dialogue than there is gore or bludgeoning. This is the first time that I’ve shot something that’s been so physically damaging to a character. Shooting a proper bludgeoning was fun to choreograph and fun to shoot it. But I think that it’s a really productive space to think about female representation in film. Women have been the subject of lots of horror stories, and I always like to remember that a teenage girl invented Frankenstein. I think that women have, have always had a place in horror, especially.