Half a century on, the main question hanging over Tod Kotcheff’s bleak outback drama is “what’s changed?”

Age has not wearied Wake in Fright, Canadian director Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 adaptation of Kenneth Cook’s controversial novel. If anything, the film has become more potent, more poignant, even more capable of shocking and disturbing. In 2021, we are grappling with toxic masculinity, structural misogyny and the horrors that the phrase “boys will be boys” has concealed. Kotcheff saw it all a half-century ago (and Cook a decade before that) and put it all up on screen. People were unhappy. The film was all but lost for decades until editor Anthony Buckley resurrected it from the original elements in the early 2000s to nigh-universal acclaim. What a difference a few decades make, hey?

Except, as I noted, the themes are as relevant as ever. Indeed, Australian cinema returns to these notions, these bleak and hateful psychological undercurrents again and again. Rowan Woods’ The Boys, Davis Michôd’s Animal Kingdom, Justin Kurzel’s Snowtown: these are the children of Wake in Fright.

For those who came in late, Wake in Fright follows the downward spiral of schoolteacher John Grant (Gary Bond), who is forced to take a post in a one room school in the tiny outback town of Tiboonda to pay back the government for his education. Heading back to Sydney for the Christmas break to see his much-missed girlfriend, he must overnight in the nearest “big city”, Bundanyabba, aka ‘The Yabba’. There he loses his money – including his fare to Sydney – in a misguided attempt to win enough to escape his teaching contract by playing two-up. Stuck in The Yabba, he surrenders himself to the town’s principal pastimes of marathon drinking, fighting, kangaroo hunting, and general brutality.

A cast of memorable grotesques are on hand to guide him, Virgil-like, on his journey. He is initiated into the town’s culture by the local cop, Jock Crawford, memorably played by Australian acting legend Chips Rafferty. It’s a stroke of casting genius to have Rafferty, a walking symbol of upstanding Australian masculinity, be Grant’s gateway into ugly male depravity. Also in the mix is Jack Thompson as Dick, one of two local miners who take Grant along on a drunken and horrifically violent kangaroo shooting trip that culminates in Grant hacking at a wounded ‘roo with a knife in a desperate bid to put the poor thing out of its misery (this is staged for the film, but actual hunting footage is also used – fair warning, animal lovers). It was Thompson’s first role and Rafferty’s last, lending the film a certain “passing of the torch” patina.

But Grant’s primary initiator into the primal, ugly world of The Yabba is the local doctor, Clarence Tydon, brought to life by a saturnine Donald Pleasence. An alcoholic and an educated man, ‘Doc’ cleaves to philosophical pretensions, slurring arch observations on the thin and fleeting nature of civilisation from time to time, but he’s just as debauched as the rest of the Yabba crew, culminating in a scene where he tries to force Grant into a drunken homosexual tryst.

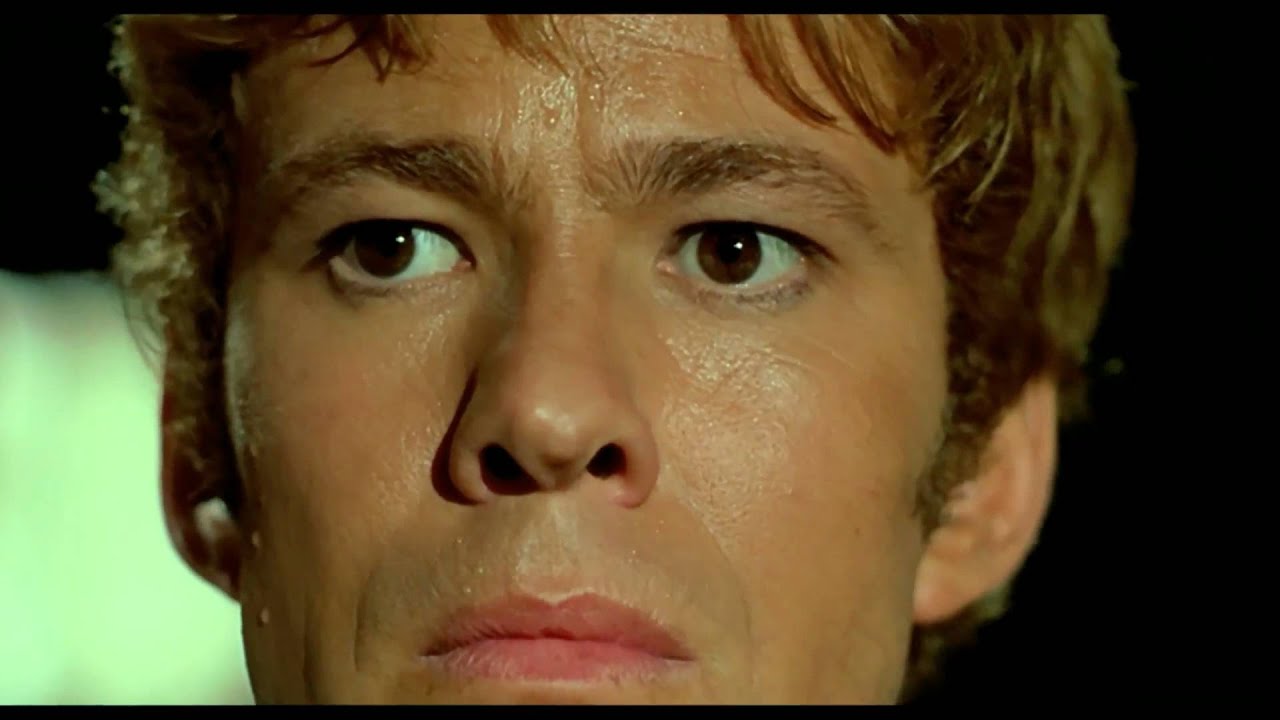

It’s ambiguous as to whether he succeeds or not, but restricting the film’s sex to nonconsensual guy-on-guy is in keeping with the strong thread of misogyny running through Wake in Fright. Not that the film itself is misogynist, but it is observing a misogynist culture in stark and lurid detail. Femininity of almost any swipe is derided, rejected, abused. Grant himself, somewhat effete with his rounded vowels, fair hair and beardless chin, is as close to a woman as the Yabba men can accept and even then, his lack of “traditional” masculinity makes him a bit of a target. Elsewhere, there’s a palpable homoerotic subtext to the playfighting between Thompson’s Dick (and let’s think about that name, hey?) and his mate, Joe (Peter Whittle). For his part, for all that he puts himself above the uneducated ruffians of The Yabba, he clearly longs for their endorsement and acceptance, eagerly adopting their ethos and prejudices. Offered sex with Janette (Sylvia Kay), the frustrated adult daughter of one of the local characters, he vomits on the verge of doing the deed. When he seemingly succumbs to Doc’s loutish, ugly advances, he’s in effect surrendering to The Yabba’s code of machismo, where even the supposed intimacy of sex must be mediated through atavistic aggression.

It’s okay, though – these things happen, mate. Boys will be boys. Mateship is the law of the land in The Yabba and its preferred currency – though Grant is almost dead broke for most of the film, he’s kept topped up with beer and opportunities to disgrace himself thanks to the kindness of his new mates. No other film has ever displayed such a keen eye for the sinister flipside of the ineffable Aussie quality of “mateship” – the way affection becomes obligation, favours become threats, and socially-enforced loyalty to near-strangers can drive a man beyond reason, self-preservation, sense. Grant becomes trapped in The Yabba not just geographically, but socially and even spiritually, bound there by a system of customs and obligations as strong as gravity. No wonder when he finally tries to escape, a misunderstanding with a truckie he cadges a lift from sees him deposited on The Yabba’s dusty main drag once more – by the filmic universe’s implied rules, he is stuck there until he discharges all the duties of mateship, for good or ill.

Director Kotcheff, whose widely meandering career encompasses films as diverse as First Blood and Weekend at Bernie’s, mounts the proceedings with an increasingly surreal shooting and editing style, pushing the formal boundaries of the film further and further as Grant gets drunker and drunker, the events more appalling. For all that Wake in Fright paints a horrifyingly accurate portrayal of the worst excesses of Australian masculinity, stylistically it’s an impressionistic psychological portrait, never quite tipping into outright fantasy, but working to keep the viewer unbalanced and off kilter.

Which has led many pundits to label the film as a horror movie, and I guess if you can align yourself with Grant and see his journey as a typical “into the bad place” terror tale, that’s a fair call. It does require you to keep yourself separate from The Yabba and its populace, though. For many viewers, however – myself included – The Yabba is not some horrifying other-place like Dracula’s Castle or the Grimm Brothers’ woods. For many who have lived in rural Australia, Wake in Fright rings true, and its depiction of masculine culture in such places may be exaggerated, but it’s also accurate. By those lights, the film is either a black comedy or a singular piece of cinematic anthropology, which on reflection makes it scarier than The Exorcist. Bleak, brutal, and boozy, Wake in Fright stares into the bloodshot eyes of the Aussie bloke and does not blink.