With the comic adaptation Bloodshot out this week and the 10th (counting Hobbs & Shaw) Fast and Furious film on the horizon, not to mention voice duties on the third Guardians of the Galaxy flick down the track, it’s safe to say that smooth-domed action hunk Vin Diesel is an established star these days.

But that wasn’t always the case. Back in the year 2000, he was a fairly unknown quantity; an actor emerging form New York City’s indie theatre and film scene with just a handful of big screen roles under his belt, including his own feature directorial debut, Strays (1997), and a supporting role in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1999). The Fast and the Furious – and the franchise it inexplicably spawned – was a year away. But in between the battlefields of Normandy and the streets of LA., Vin took a side trip to outer space with a role in the low-budget sci-fi thriller, Pitch Black, and while street-racing thief Dom Toretto may be his most famous role, night-fighting killer Richard B. Riddick is by far his coolest.

Aliens meets Stagecoach

Directed by genre veteran David Twohy, who rewrote an original script by Ken and Jim Wheats, Pitch Black takes place in the indeterminate future, when a spaceship full of cryogenically frozen passengers crash-lands on a barren desert world.

The survivors are a mixed bunch: pilot Fry (Radha Mitchell), prospectors Shazza (Claudia Black) and Zeke (John Moore), effete art merchant Ogilvie (Lewis Fitz-Gerald), runaway Jack (Rhiana Griffith), Muslim preacher Imam (Keith David) and his three young acolytes and – most importantly for our purposes – bounty hunter Johns (Cole Hauser) and his prisoner, dangerous killer Richard B. Riddick (our man Vin), a taciturn, shaven-headed murder machine with a fondness for knives and eyes that have been surgically altered for night vision (he has to wear cool-lookin’ goggles in normal light).

Those gnarly eyes come in handy when the desert planet’s three suns undergo an eclipse and suddenly our ragtag band are beset by swarms of huge, nocturnal, carnivorous, flying monsters that look like a cross between a pterodactyl and a hammerhead shark, all hellbent on eating the only available prey – our heroes (lord knows what they eat otherwise, but let’s not dwell on that). Our disparate and desperate group are forced to rely on each other for survival – and that includes the brutal Riddick.

Pitch Black’s storyline isn’t too new – the idea of a mixed bag of characters being thrust together in hostile territory goes back to at least John Ford’s seminal Western, Stagecoach (1939), and ravening hordes of aliens have been a genre staple forever, but for modern audiences the prime example is James Cameron’s Aliens (1986) (Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien only has the one critter). However, sometimes it’s not what you do, but the way that you do it, and while Pitch Black may lose points for originality, it makes up for it with style and attitude.

B-movie bliss

David Twohy had only directed two movies when he stepped up to helm Pitch Black, but he had plenty of screenplays under his belt, including Warlock (1989), The Fugitive (1993), and Waterworld (1995). Perhaps it was that last one that taught him the value of brevity and speed; on the page, Pitch Black is a stunningly lean film, stripped of all but the most essential exposition and characterisation, and trusting a genre-savvy audience to pick up on the quickly-sketched scenario.

Instead of story complexity, what we get is action, atmosphere and style. Pitch Black was filmed in the merciless desert around Coober Pedy, South Australia, which had previously subbed in for Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome’s post-apocalyptic wasteland and Red Planet’s Mars. Cinematographer David Eggby shoots the daylight scenes in harsh, bleached tones and the post-eclipse sequences in deep chiaroscuro as the characters use whatever available light they have – neon tubes, torches, flames, and whatever else – to keep the photophobic creatures at bay. This allows for some striking shots; at one point a wounded victim spits alcohol in a flaming torch, the flare revealing the monsters crouched around him ready to pounce.

But the real appeal is Diesel’s Riddick.

Conan in space

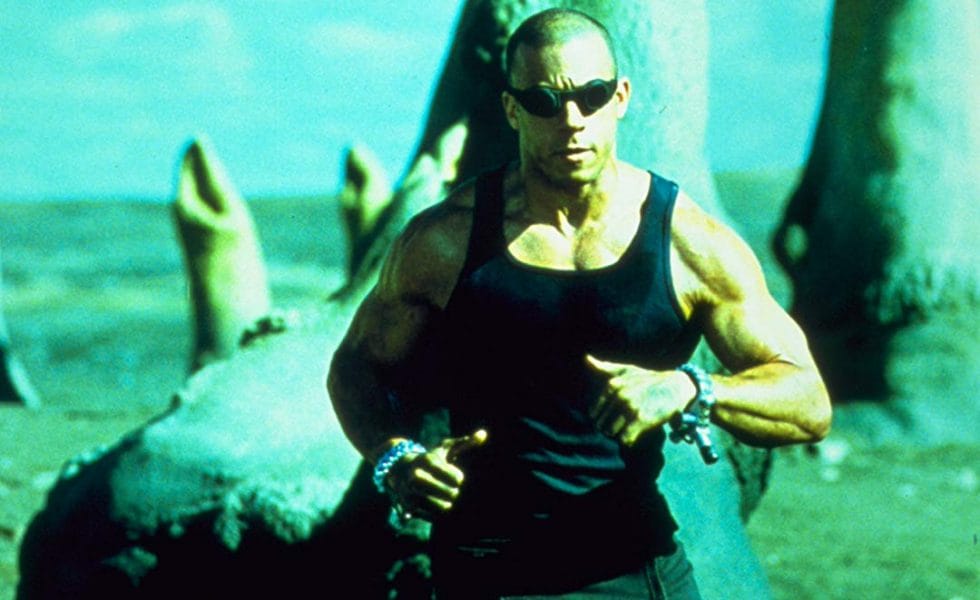

With his bald scalp, welder’s goggles, muscle top and deadpan, basso delivery, Riddick is an instantly iconic figure. He’s a John Carpenter character, really; his distinctive look and nihilistic disdain for authority recalls Snake Plissken in Escape From New York (1981), while the way in which he gradually moves forward to lead the ensemble mirrors how MacReady grew to prominence over the course of The Thing (1982) – both characters played by the notably more hirsute Kurt Russell. Taking us back to Stagecoach, his role is similar to John Wayne’s Ringo Kid in that film – also an outlaw who is pressed into heroism as circumstances grow dire.

Still, what Riddick really is – and subsequent films support this – is Conan the Barbarian in space; a savage warrior ill-suited to civilisation, but death on legs when the chips are down. While his look may be pure late ‘90’s industrial cyberpunk, his attitude, his capacity for violence, his love of blades and his ruthlessly stoic approach to the business of survival marks him as a direct descendant of Robert E. Howard’s Cimmerian hero. Take a look at the climax of Riddick (2013), where our guy fights off monsters from a rain-lashed basalt peak lit by lightning – it might as well be a Frazetta painting.

Unlikely franchise

And like Conan, Riddick has been unable to really get into a franchisable groove, despite the existence of two more live action movies – the aforementioned Riddick and 2004’s ambitious but daft The Chronicles of Riddick – as well as a scattering of animated and video game offerings. Chronicles, a sprawling space opera that’s like a goth version of Flash Gordon, falters because the expanded universe depicted doesn’t stand up to close scrutiny and you’re never quite sure whether the whole exercise is camp or serious business, while Riddick has its charms, but is largely a back-to-basics rehash of the first film.

Which we will always have. The Riddick franchise exists seemingly through the sheer willpower of its star, who always seem to be having The Most Fun when he’s slicing up alien monsters and emoting through smoked glass goggles, even if the films themselves aren’t as enjoyable for the audience. Still, the original Pitch Black has aged into a bona fide B-movie masterpiece, lean, muscular, and lethal – just like its MVP.